Electoral Insight – Electoral Participation of Ethnocultural Communities

Electoral Insight – December 2006

Seeking Inclusion: South Asian Political Representation in Suburban Canada

Andrew Matheson

M.A., Immigration and Settlement Studies, Ryerson University

This study sets out to explain the variables that have created a political opportunity structure more favourable for visible-minority politicians and candidates in Canada's suburban peripheries than in urban centres. The research analyzes the rates of visible-minority representation with special attention to South Asian politicians in the Toronto suburbs of Mississauga and Brampton, who, after the 2006 general election, achieved some of the highest rates of visible-minority political representation in the country. The study concludes that a variety of factors have led to this more favourable suburban political opportunity structure, including dense residential concentrations, strong socio-economic status and acculturation variables, and lower incumbency rates.

Most people think of North America's major cities as hubs of ethnocultural diversity surrounded by the blanket whiteness of the suburbs. Yet in Canada, federal electoral ridings in suburban centres have proven to be the most receptive to visible-minority politicians. In the most recent 2006 general election, 24 visible-minority candidates were elected to the 308-seat House of Commons. While 8 of these politicians represent ridings in Canada's three largest urban centres – Montréal, Toronto and Vancouver – a surprising 12 represent suburban constituencies surrounding these cities. Furthermore, the overwhelming majority of these suburban representatives are of South Asian descent.

Using the suburban cities of Mississauga and Brampton as a case study, this paper sets out to answer two important questions: Why have the political opportunity structures in suburban centres proven to be more favourable for visible minorities than those in major urban centres such as Toronto and Vancouver? And why have South Asian politicians succeeded in achieving levels of political representation proportional to their presence in the general population, while so many other visible-minority communities, especially Canada's Chinese and Black populations, have not?

Measuring visible-minority political representation

Measuring ethnicity and race is by nature a complicated problem, and one that has no easy solution. For the purpose of this study, the definition of "visible minority" adheres to that used by Statistics Canada during the 2001 Census – a generally accepted definition, albeit with its own complications. Statistics Canada defines visible minorities as people who are "non-Caucasian in race or non-white in colour." Footnote 1 Excluded from this definition are members of Aboriginal nations. With this definition in mind, extensive biographical and photographic analysis was conducted to reach the figure of 24 visible-minority politicians; a number that includes South Asians, Chinese, Blacks, Arabs, Japanese and Latin Americans, but excludes the Aboriginal members of the 39th Parliament. It also includes two politicians of mixed Chinese and European ancestry.

The relationship between statistical representation and substantive representation has shown itself to be relatively ambiguous and unpredictable. In their 2002 study, Siemiatycki and Saloojee argue that the presence of visible minorities in political bodies does not necessarily lead to diversity-friendly policy measures. Footnote 2

In spite of this possibility, Simard argues that political representation is still "an issue of the utmost importance for the future of democracy," Footnote 3 especially a democracy in which visible minorities are expected to become the statistical majority, if they are not already, in most of Canada's major metropolitan areas. Beyond the creation of policy measures and the drafting of legislation, political representation also carries with it symbolic importance, especially in a nation of immigrants. With wave after wave of immigrants arriving in Canada and the resulting demographic changes that have occurred, it is crucial that all communities, regardless of race, ethnicity or country of origin feel they have access to the political system, as well as any other aspect of Canadian society, if they so choose; such is the mandate set out in the Canadian Multiculturalism Act. Drastically unrepresentative political bodies, therefore, need to be viewed as partial indicators of social exclusion and disenfranchisement, as well as a "serious threat to our shared notion of participatory democracy." Footnote 4

Where they are getting elected – the suburbs

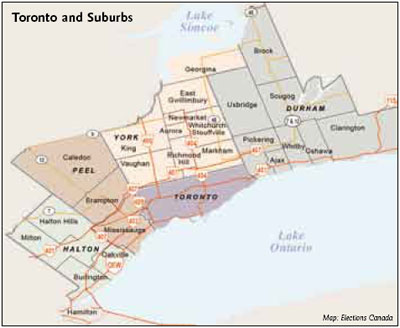

Toronto, traditionally viewed as Canada's most diverse city, is being outperformed by its suburban neighbours when it comes to electing visible-minority politicians. While 9 of the 24 visible-minority MPs in the 39th Parliament were elected in the Greater Toronto Area, only 2 were victorious in the City of Toronto proper, while 5 were victorious in the suburban cities of Mississauga and Brampton, and another 2 in rural/suburban ridings in the outer regions of Halton and Durham. Only York Region, containing both suburban cities and rural areas north of Toronto, elected a lower percentage of visible-minority MPs than the City of Toronto did.

| Location | No. of ridings | No. of visible-minority MPs elected | % of seats held by visible minorities |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brampton | 3 | 2/3 | 67 |

| Mississauga | 5 | 3/5 | 60 |

| Durham Region | 4 | 1/4 | 25 |

| Halton Region | 4 | 1/4 | 25 |

| Toronto | 23 | 2/23 | 9 |

| York Region | 6 | 0/6 | 0 |

Data on MPs supplied by author

With one third as many seats as the City of Toronto, the suburbs of Brampton and Mississauga still managed to elect more than twice as many visible-minority candidates as Toronto. So why are Toronto's suburbs outpacing their big city neighbour?

Canada's suburbs have witnessed dramatic population explosions over the course of the last decade. Increasingly more immigrants are choosing to settle in Canada's suburbs instead of its major cities. In 1998, for example, 82.4% of new immigrants to the Greater Toronto Area and Hamilton settled in the City of Toronto, while 9.7% chose to settle in the Region of Peel (made up of Mississauga, Brampton and the largely rural town of Caledon). Footnote 5 By 2003, however, 20.9%, or one fifth, of all new immigrants to the area were deciding to make Peel Region their home, a more than twofold increase, while 63.7% chose Toronto, a decrease of almost one quarter.

One of the most daunting variables for new faces in the political system is the incumbency factor. Footnote 6 The effects of recent growth rates in the suburbs on the distribution of federal electoral districts have served to loosen incumbent strongholds that make most of Toronto's federal ridings inaccessible to new visible-minority candidates.

The rapid growth of the cities of Brampton and Mississauga over the last few decades has led not only to a constant reshuffling of federal electoral districts, but also to the addition of brand new ridings, making incumbent footholds far less rooted in the suburbs than they are in the City of Toronto.

In fact, not one of the current visible-minority MPs in Mississauga or Brampton had to run against an incumbent to secure a seat in the House of Commons.

Mississauga and Brampton held eight federal ridings during the last general election of 2006 – a far cry from the three federal ridings that existed in the two cities in 1980. The same cannot be said for the City of Toronto, where in the last 25 years the number of federal ridings has grown by only one. Although riding boundaries were often readjusted, this did not occur simultaneously with any significant increase in the number of ridings, therefore making new candidates in the cities more reliant upon incumbent retirement and party sweeps.

Even in a participatory democracy such as Canada, socio-economic status is also often considered to be one of the key variables in political participation. High campaign costs make it more difficult for those with lower income to mobilize the necessary funds to run for political office. Footnote 7 Furthermore, with voting participation closely linked to home ownership, Footnote 8 higher rates of poverty will inevitably have a negative effect on a community's mobilization and reduce that community's numbers at the polls. Although Peel Region's Planning, Policy and Research Division is concerned with growing income gaps between recent immigrants and non-immigrants, generally speaking, the socio-economic disadvantage that burdens so many ethno-racial groups in the City of Toronto does not exist in the suburbs. Footnote 9 These are socially mobile communities more readily able to gain access to a political system that often associates political success with the accumulation of wealth.

Who is getting elected – South Asian Canadians

Elected in 1957, Douglas Jung served two terms as Canada's first member of Parliament of Chinese descent.

In 1993, three politicians simultaneously became the first members of Parliament of South Asian descent in the Canadian House of Commons. While this was a monumental first for Canada's South Asian community, the event was somewhat tardy in relation to milestone political firsts of Canada's other visible-minority communities. Some 25 years earlier, in 1968, Canada's first Black MP (Lincoln Alexander) and Arab MP (Pierre De Bané) first entered the House, and more than three and a half decades earlier, Canada's first MP of Chinese descent (Douglas Jung) was victorious in securing his place among the members of Canada's 23rd Parliament in 1957.

During the most recent general election of 2006, South Asian candidates held strong and repeated their electoral success of 2004 by securing 10 seats in Canada's lower house. With 8 of these 10 South Asian politicians able to speak Punjabi, the language is the fourth most widely spoken in the House. Only Rahim Jaffer (Edmonton–Strathcona) and Yasmin Ratansi (Don Valley East), both Ismaili-Muslims from the South Asian diaspora in continental Africa, do not speak Punjabi.

In spite of their laggard debut, in less than a decade and a half Canada's South Asian community has made the transition from being completely under-represented to achieving a level of representation in the House of Commons proportional to their numbers in the general population. Holding 3.3% of the seats in the House of Commons, and comprising 3.1% of Canada's population, South Asians have become the largest visible-minority community in Canada to achieve such a level of representation at the federal level. They create a stark contrast to Canada's Chinese community, which, at 3.7% of the general population, holds a mere 1.6% of the seats in the House of Commons. Interestingly enough, as Table 2 highlights, Canada's Arab and Japanese populations are the only other visible-minority communities that have achieved representation in the House of Commons proportional to their populations, although their numbers are on a smaller scale.

| Minority community | MPs in 39th Parliament | % of seats in Parliament | % of general population |

|---|---|---|---|

| South Asian | 10 | 3.3 | 3.1 |

| Chinese | 5 | 1.6 | 3.7 |

| Black | 4 | 1.3 | 2.2 |

| Arab | 3 | 1.0 | 0.7 |

| Latin | 1 | 0.3 | 0.7 |

| Japanese | 1 | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| Filipino | 0 | 0.0 | 1.0 |

Data on MPs supplied by author; population statistics from 2001 Census, Statistics Canada

Why has Canada's South Asian community been more successful in entering the halls of Parliament than other visible-minority communities? Factors such as residential concentration, socio-economic status, language ability and community mobilization in the face of perceived societal discrimination have all heavily influenced the representation rates of South Asian Canadians.

Canada's South Asian population, and more specifically Canada's Sikh population, live in heavily concentrated communities, which may help explain why the majority of Canada's South Asian politicians are Sikh, comprising 7 of the 10 South Asian MPs in the House of Commons. Of these seven politicians, two represent ridings in suburban Mississauga and two in suburban Brampton. None are from the City of Toronto. If we compare the residential concentrations of Sikhs in these three communities, the connection between residential concentration and electoral success becomes clearer.

| Location | No. of Sikh MPs | Total population | % of South Asian residents | % of Sikh population (provincially) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brampton | 2/3 | 325,428 | 19.5 | 32.9 |

| Mississauga | 2/5 | 612,925 | 14.9 | 22.4 |

| Toronto | 0/23 | 2,481,494 | 10.3 | 21.5 |

Data on MPs supplied by author; population data from 2001 Census, Statistics Canada

In the City of Toronto, numerous ethnic and visible-minority groups live in similar concentrations. For example, the three largest visible-minority communities in the City of Toronto comprise relatively similar percentages of the total population: the Chinese stand at 10.6%, South Asians at 10.3% and Blacks at 8.3%. Although 21.5% of Ontario's Sikhs live in Toronto, they have been unable to use these numbers to their advantage as well as their suburban counterparts have, since they do not constitute a single dominant minority group.

Meanwhile, both Brampton and Mississauga boast high concentrations of Sikh Canadians. Such residential concentrations typically result in an extensive system of community organizations and common places of gathering. This dense social network, centred around Sikh temples (known as gurdwaras) and cultural groups, has a strong impact on the political socialization and mobilization of the Sikh community and increases the likelihood that a Sikh politician will emerge victorious due to the increased political clout of the community. Footnote 10

At a stadium in Toronto, thousands of Sikhs celebrate Baisakhi, one of their most important religious and cultural festivals.

Traditional socio-economic and cultural factors also help explain the increased rates of Sikh political representation at the federal level. Canada's Sikh community is one of the most affluent visible-minority communities in Canada, which makes it more likely that candidates will be able to afford higher campaign costs. In addition, knowledge of the English language and familiarity with democratic processes also tend to be higher among Sikh immigrants from India, than among immigrants from other countries without British colonial pasts, such as mainland China, making transitions into the Canadian political system easier. This familiarity helps explain why foreign-born South Asians, including Sikhs, are more likely to vote than their Chinese counterparts Footnote 11 and why, although they constitute Canada's largest visible-minority group, the Chinese community has half as many representatives in Parliament as Canada's South Asian community.

Finally, political events outside Canada may have had an effect on the social identity of Sikhs, which resulted in a greater incentive to involve themselves in the political process.

Writer Tarik Ali Khan argues that the storming of the Golden Temple of Amritsar in 1984 and the subsequent political fallout from this event were the root causes of increased Sikh political participation in Canada. Footnote 12 After the temple was stormed under the orders of Indira Gandhi, the Khalistan movement pushing for the independence of the state of Punjab gained momentum. Ali Khan argues that this movement, coupled with the Air India bombing in 1985, led to the stereotyping of Sikhs as "terrorists" and to racial profiling by Canadian authorities of Sikh refugee claimants. He believes that, to shed this negative stereotype, Canada's Sikh community mobilized and began working to show the Canadian public that they were model citizens.

In 1986, Moe Sihota was the first Indo-Canadian elected to a legislature in Canada (British Columbia).

It is perhaps then not coincidental that the history of South Asian Canadians in legislatures and Parliament began shortly thereafter, when Moe Sihota became the first Indo-Canadian elected to the Legislative Assembly of British Columbia in 1986, and the first Sikh Canadian elected to any provincial legislature. His victory was repeated by Ismali Murad Velshi in 1987 and Gulzar Cheema in 1988, who became the first South Asians to enter the Ontario and Manitoba legislative assemblies, respectively. Community mobilization based on fear of pending societal exclusion may have led to the increased political participation of Canada's Sikh community.

Conclusion

In spite of these recent successes, and all the variables that have led to the increased representation of South Asians in the Canadian political system, it cannot be forgotten that the general picture of visible-minority political representation in Canada is bleak. Across the nation, and in the House of Commons, the most prevalent trend is that of visible-minority under-representation. As our country continues to diversify, it becomes more and more crucial to ensure that our elected political bodies diversify alongside them. The governance of one of the most diverse countries in the world by predominantly homogeneous political bodies runs counter to the Canadian Multiculturalism Act, which calls for the equality of all Canadians in all aspects of society, whether it be economic, social, cultural or political. Canada still has a long way to go before the vision set out in the Act is realized, although the suburbs, at least in the case of the Greater Toronto Area, seem to be the trailblazers in promoting greater levels of inclusion in the Canadian political system. Far from demanding Anglo-conformity, Brampton and Mississauga have emerged from the suburban stereotype and have become rare sites of visible-minority proportional representation in Canada.

Notes

Return to source of Footnote 1 Statistics Canada, 2001 Community Profiles. Released June 27, 2002. Last modified: 2005-11-30. Statistics Canada Catalogue No. 93F0053XIE.

Return to source of Footnote 2 Myer Siemiatycki and Anver Saloojee, "Ethnoracial Political Representation in Toronto: Patterns and Problems," Journal of International Migration and Integration Vol. 3, No. 2 (Spring 2002), pp. 241–273.

Return to source of Footnote 3 Carolle Simard, Ethnic Minority Political Representation in Montreal. Paper presented at the Fourth National Metropolis Conference (March 2000), Toronto, Ontario.

Return to source of Footnote 4 Annamie Paul, "Under-representation in Canadian Public Institutions: Canada's Challenge," Canadian Issues (Summer 2005), pp. 18–21.

Return to source of Footnote 5 Social Planning Council of Peel, "Immigrants and Visible Minorities in Peel," Infoshare Vol. 11, No. 1 (May 2003).

Return to source of Footnote 6 Daiva K. Stasiulis and Yasmeen Abu-Laban, "The House the Parties Built: (Re)constructing Ethnic Representation in Canadian Politics," in Kathy Megyery, ed., Ethno-Cultural Groups and Visible Minorities in Canadian Politics: The Question of Access (Toronto: Dundurn Press, 1991).

Return to source of Footnote 7 Siemiatycki and Saloojee, "Ethnoracial Political Representation."

Return to source of Footnote 8 Siemiatycki and Saloojee, "Ethnoracial Political Representation."

Return to source of Footnote 9 Stasiulis and Abu-Laban, "The House the Parties Built."

Return to source of Footnote 10 Stasiulis and Abu-Laban, "The House the Parties Built."

Return to source of Footnote 11 Livianna Tossutti, "Electoral Turnout and Canada's Changing Cultural Makeup: Interviews with Three Municipal Leaders," Canadian Issues (Summer 2005), pp. 53–56.

Return to source of Footnote 12 Tarik Ali Khan, "Canada Sikhs," Himāl South Asian Vol. 12, No. 12 (December 1999), <http://www.himalmag.com/99Dec/sikhs.htm>.

Note:

The opinions expressed are those of the authors; they do not necessarily reflect those of the Chief Electoral Officer of Canada.