Electoral Insight – Electoral Participation of Ethnocultural Communities

Electoral Insight – December 2006

Political Engagement Among Immigrants in Four Anglo-Democracies

Antoine Bilodeau

Assistant Professor, Department of Political Science, Concordia University

Mebs Kanji

Assistant Professor, Department of Political Science, Concordia University

Since the 1960s, immigrants to Canada and other Western democracies increasingly come from countries with political cultures very different from those in the host country. This paper examines whether these new waves of immigrants now living in Canada and three other Anglo-democracies (the United States, Australia and New Zealand) become interested in, attentive to and knowledgeable about the politics of their host country. This brief review of political engagement among immigrants offers some reassuring findings. The new waves of immigrants appear to have adapted successfully. They have developed levels of interest in, attention to and knowledge of politics that are at least as high as those of the local population. Moreover, these results are not unique to Canada and are replicated within the three other Anglo-democracies examined.

Immigration patterns in Western democracies have changed significantly since the 1960s, Canada being no exception. Up to the 1960s, immigrants originated mainly from Western, Northern and Southern Europe; immigrants nowadays, however, originate from Eastern and Central Europe, Asia, Africa and Latin America. There are reasons to suppose that these new waves of immigrants may experience greater challenges integrating into their new political environment than the older waves of immigrants. Whereas immigrants in the past originated from democracies with political cultures resembling those in the host country, newer waves of immigrants come from countries with political cultures that are very different, most even non-democratic.

In this paper, we examine how immigrants from such non-traditional source countries are adapting to their new political environment. In particular, we investigate three key questions. First, how interested are immigrants in the politics of their host country? Second, how attentive are they to politics in the mass media? And third, how much do they know about the politics of their host society? Our aim is to compare the political engagement of immigrants from non-traditional source countries to that of earlier waves of immigrants and members of the local population. Our primary concern is with immigrants in Canada. However, in the latter part of the paper, we briefly compare the Canadian situation to that of other Anglo-democracies that have experienced similar changes in their immigration, namely the United States, Australia and New Zealand.

The data for our investigation are drawn from election studies in each of these countries. Footnote 1 Such studies, when pooled over several years, provide a rich resource for exploring the political orientations and behaviours of immigrants. The limitation of working with these data, however, is that they do not permit us to examine how immigrants adapt to their new political environment immediately upon arrival. Because the samples of the election studies are representative and obtained using a random process, the immigrant respondents included in the samples have lived in the host countries for many years. For instance, in our Canadian sample, immigrants have lived in Canada for an average of 31 years. Our analysis, therefore, focuses on immigrants who are presumed to have settled down and are not in the initial process of adapting to their host society. Also, there is an important difference between our samples of immigrants from traditional and non-traditional source countries, in that the former have resided in Canada for an average of 38 years and the latter for 24 years. While this difference needs to be kept in mind, it is important to note that for the most part it does not explain the differences in political engagement between the two groups of immigrants that are presented below. Footnote 2

Why should we care if immigrants participate in politics?

To this point, little attention has been given to the question of how well immigrants adapt to their political environment. After all, why should we care if immigrants participate in politics? This might not be such an important concern, were we certain that the needs and preferences of immigrants were already adequately represented within the host society. However, because the new waves of immigrants come from societies with different cultures, there are reasons to suppose that their needs and preferences may be different from those of earlier immigrants and native-born citizens. Consequently, there is a very real possibility that immigrants from non-traditional source countries may not see their views adequately represented in the host society if they do not participate in the political process.

Participation in politics, such as voting, attending political meetings or working for a party or local candidate, is contingent on a host of important factors, including interest in politics, exposure to information and political knowledge, to name a few. Footnote 3 Without these basic essentials, citizens may not have the necessary motivation to partake in politics, nor the wherewithal to make the connections between their needs and concerns, and the best choices to help them attain desired policy outcomes. In examining how immigrants adapt to politics in the host society, the way to start, therefore, is by studying the extent to which immigrants are interested, informed and knowledgeable about politics.

Interest in politics in Canada

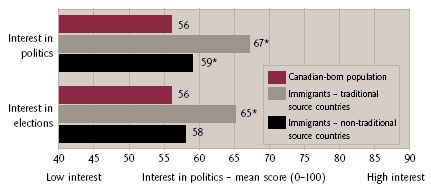

The data in Figure 1 indicate that not all immigrants share the same degree of interest in politics. Immigrants from traditional source countries have a greater degree of interest in politics than immigrants from non-traditional source countries, but what is more striking is that both groups of immigrants turn out to be somewhat more interested in politics than the Canadian-born population. More specifically, on a scale that ranges from 0 to 100, where 0 indicates low interest in politics and 100 indicates high interest, the average interest in politics for immigrants from traditional source countries is 67. For immigrants from non-traditional source countries, the average is 59. And for citizens born in Canada, the average level of interest in politics is 56.

Figure 1

Interest in Politics and Elections

Source: 1993, 1997, 2000 and 2004 Canadian Election Studies (pooled sample – Canadian-born population, n = 10,139; immigrants from traditional source countries, n = 694; immigrants from non-traditional source countries, n = 569)

*Difference from Canadian-born population is statistically significant at least at .10-level (t-test).

The findings for interest in elections closely resemble those for politics more generally. Immigrants from non-traditional source countries manifest a more modest level of interest in elections than those from traditional source countries, but no less interest than the Canadian-born population. Hence, regardless of whether we examine interest in politics more generally or interest in a specific aspect of politics, we find similar trends.

Attention paid to political information in the media

Being interested in politics is an important step toward being politically engaged; however, participating in politics also requires being adequately informed. The next part of our analysis, therefore, examines how much attention Canadians pay to political information in the media.

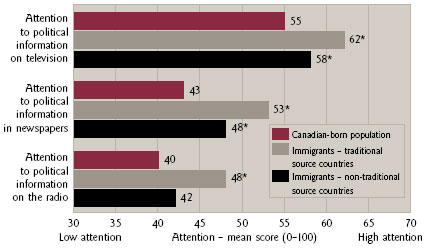

The findings reported in Figure 2 indicate that, regardless of the specific medium they use – television, newspapers or radio – immigrants, including those from non-traditional source countries, pay either as much or greater attention to information about politics as does the Canadian-born population. However, the findings also show that immigrants from traditional source countries generally pay greater attention to politics than those from non-traditional source countries.

Figure 2

Attention to Political Information in Mass Media

Source: 1993, 1997, 2000 and 2004 Canadian Election Studies (pooled sample – Canadian-born population, n = 11,906; immigrants from traditional source countries, n = 819; immigrants from non-traditional source countries, n = 615)

*Difference from Canadian-born population is statistically significant at least at .10-level (t-test).

Using various information sources, immigrants, particularly those from traditional source countries, pay as much attention to politics and elections as those born in Canada – and often more.

Moreover, these data show that most Canadians, regardless of where they were born, have similar preferences when it comes to their favourite media for acquiring political information. The source of political information most often identified is television, newspapers are the second most preferred information source and radio is the least preferred. More specifically, on a scale ranging from 0 to 100, where 0 means little attention to political information and 100 means maximal attention, Canadian-born respondents score an average of 55 on attention paid to politics on TV; 43 on attention paid to politics in newspapers; and 40 on attentiveness to politics on the radio. Similarly, for immigrants from traditional source countries, the average scores are 62, 53 and 48. And for immigrants from non-traditional source countries, the average scores are 58, 48 and 42.

Another intriguing finding is that, although the Canadian-born population lags behind most immigrants on attention paid to politics in various news media, the gaps are the largest in attentiveness to politics in newspapers. This is an interesting finding because newspapers are a rich source of information, especially in terms of analysis and editorial content. What these data suggest, therefore, is that immigrants are not only more exposed to political information than the Canadian-born population, but that they are also more exposed to information of better quality.

Knowledge of Canadian politics

The findings presented so far suggest that immigrants from non-traditional source countries are no less interested in or attentive to politics than their Canadian-born counterparts. But what about knowledge of politics?

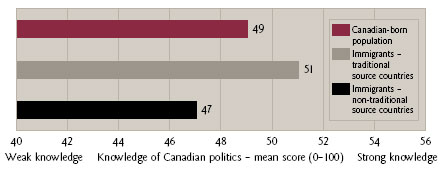

To measure knowledge of Canadian politics, we rely on a battery of questions that ask respondents to identify various political figures, such as the Minister of Finance in Ottawa, the premier in the respondent's province and the first woman to be prime minister. The average knowledge scores reported in Figure 3 range from 0–100, where 100 represents strong knowledge of Canadian politics and 0 represents weak knowledge. Footnote 4

Figure 3

Knowledge of Canadian Politics

Source: 1997, 2000 and 2004 Canadian Election Studies (pooled sample – Canadian-born population, n = 6,831; immigrants from traditional source countries, n = 462; immigrants from non-traditional source countries, n = 350)

The differences between either group of immigrants and the Canadian-born population are not

statistically significant.

Surprisingly, although they are more interested in and attentive to politics, immigrants are not more knowledgeable than the local population. The evidence shows that there are no significant differences in knowledge levels among the three groups of respondents. Canadian-born respondents score an average of 49 on the knowledge index, and immigrants from traditional and non-traditional source countries score 51 and 47, respectively. When it comes to recollecting different political figures, therefore, our findings indicate that immigrants, including those from non-traditional source countries, are no less knowledgeable than their Canadian-born counterparts. It is striking that, despite their higher levels of political interest and attention to media (especially newspapers), immigrants are not more knowledgeable about politics than are members of the local population. It is plausible that immigrants' levels of knowledge might be weaker than those of the local population if it were not for their greater interest in and attention to politics. More in-depth analysis is required to further investigate this possibility.

Interest in politics in four Anglo-democracies

The findings presented above seem to suggest that immigrants from non-traditional sources adapt remarkably well to their new political context, despite coming from societies with different political cultures. However, Canada is not the only country that hosts large proportions of immigrants. Are immigrants in other Anglo-democracies (the United States, Australia and New Zealand) also adapting as successfully to the new political cultures in their respective host societies?

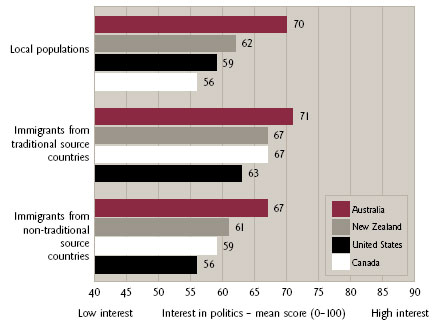

Due to space limitations, our analysis in this instance is limited solely to an examination of interest in politics. Still, the findings are revealing in several respects. First, the cross-national perspective provided in Figure 4 suggests that Canadians are among the least interested in politics when compared to citizens in other Anglo-democracies. This finding is consistent for the local populations as well as for both groups of immigrants. Only immigrants in the United States are less interested in politics than immigrants in Canada.

Figure 4

Interest in Politics in Four Anglo-Democracies

Sources: Canadian Election Studies (1993–2004); American Election Studies (1986–2000); Australian Election Studies (1993–2004); New Zealand Election Studies (1990–2002)

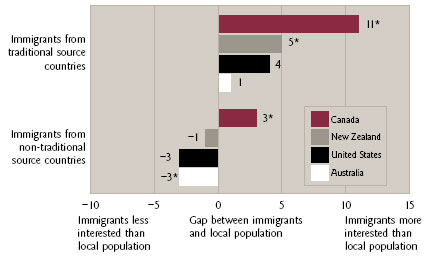

Second, when we compare the results for immigrants against local populations, we find that the gaps in interest levels between Canadian-born respondents and immigrants stand out from those in other countries. Immigrants from traditional source countries typically exhibit more interest in politics than local populations (see Figure 5). And immigrants from non-traditional source countries have broadly the same levels of interest in politics as members of the local population. Note, however, that immigrants from traditional source countries in Canada exhibit higher levels of interest in politics relative to the Canadian-born population than do immigrants from similar points of origin in other Anglo-democracies. More specifically, the gap between immigrants from traditional source countries and the local population is 11 points in Canada, 5 points in New Zealand, 4 points in the United States, and there is only a 1-point difference in Australia. Note also that only in Canada do immigrants from non-traditional source countries exhibit higher levels of interest in politics than the local population. These latter differences are not as large as those between immigrants from traditional source countries and local populations, but it is revealing nonetheless that this particular difference is positive only in Canada.

Figure 5

Interest in Politics in Four Anglo-Democracies

(comparison of immigrant and local populations)

Sources: Canadian Election Studies (1993–2004); American Election Studies (1986–2000); Australian Election Studies (1993–2004); New Zealand Election Studies (1990–2002)

*Difference from local population is statistically significant at least at .10-level (t-test).

A young woman serves as an information officer at an Ottawa polling station during the 2006 election.

There may be several explanations for these differences. First, immigrants in Canada may appear more interested in politics than immigrants in other Anglo-democracies because the Canadian-born population is less interested than local populations in other countries. Second, there may be differences in the pools of immigrants that settle to different societies and these distinct pools of immigrants could explain higher levels of interest in politics among newcomers in Canada. Immigrants, even within our subcategories (traditional and non-traditional), do not form a homogeneous group and it is possible, therefore, that differences in demographic background and varying socialization experiences may be partly at work. Third, it is possible that immigrants in Canada have better integrated into their host society than immigrants in other Anglo-democracies in terms of education, income and employment, factors that are associated with a greater interest in politics. These possibilities would need to be considered in future research. Footnote 5

Conclusion

New waves of immigrants are settling in Canada and other Western democracies. Because these new immigrants come from countries with political cultures that are very different from those in the host country, we expected that they would encounter some difficulties adapting to the politics of their host country. We certainly did not expect these newcomers to remain forever apolitical, but neither did we expect that they would be as preoccupied with politics as earlier immigrants from more traditional sources or members of the local populations. This brief review of political engagement among immigrants in Canada and three other Anglo-democracies offers some findings that run contrary to our initial expectations. Immigrants from non-traditional source countries who have been settled in their host-society for an average of more than two decades are not as politically engaged as immigrants from more traditional source countries, but they are nonetheless as engaged in politics as local populations are. In short, immigrants from non-traditional source countries appear as interested in politics, as attentive to politics in the news and as knowledgeable about politics as locals who were born and socialized in the host societies.

Based on these findings, therefore, should we conclude that new waves of immigrants adapt successfully to the politics of their host societies once they have been settled for an extended period of time? Adopting such a conclusion, at this stage of the analysis, would be premature. This paper provides some optimistic evidence about immigrants' political integration in Canada and in other Anglo-democracies, but much remains to be learned. The road to political integration is long and complex. Basic questions remain to be answered, such as, how long exactly must newcomers be in a host society before they start to engage in politics? And, what settlement issues do they need to tackle before they start participating? Other crucial questions concern whether new waves of immigrants become actively involved in the political process and which channels of participation they prefer and are most able to use. These and other important matters still need to be examined. At stake is not only the vitality of our democracy but access to a political voice for an increasing proportion of new Canadians.Notes

Return to source of Footnote 1 For each country, several election studies were pooled together: Canada: 1993–2004; United States: 1986–2000; Australia: 1993–2000; New Zealand: 1990–2002. The pooled sample in Canada includes 12,267 people born in Canada, and 850 and 631 immigrants from traditional and non-traditional source countries. The samples are respectively 9,922, 153 and 395 for the United States; 7,938, 1,596 and 964 for Australia; and 15,785, 2,372 and 529 for New Zealand.

Return to source of Footnote 2 That most immigrants have lived many years in the host countries does not imply that they are older than the local population. The average age for immigrants from traditional and non-traditional source countries is 55 and 46 years old, while that for the local population is 45. Multivariate analyses demonstrate that these age differences do not explain the differences in political engagement between the three groups of respondents (results not presented).

Return to source of Footnote 3 Sidney Verba, Kay Lehman Schlozman and Henry E. Brady, Voice and Equality: Civic Voluntarism in American Politics (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1995).

Return to source of Footnote 4 The knowledge index ranges from 0 to 100 and indicates the number of correct answers to three factual questions: 0 for no correct answer, 33 for one correct answer, 67 for two correct answers and 100 for three. The numbers reported in Figure 3 are the average scores for each of our three groups of respondents.

Return to source of Footnote 5 Are immigrants in Canada also doing better than immigrants in other Anglo-democracies in terms of attention to politics in the media and knowledge of politics? It is difficult to answer this question, not only because of the limited space provided here, but also because of methodological considerations. With regard to knowledge of politics, the other countries examined do not offer satisfactory indicators of political knowledge. And concerning attention to politics in the media, significant variations in the questions asked in the four countries make it difficult to answer the question with certainty. However, a brief examination of the data suggests that the findings for interest in politics are not replicated for media attention (not presented). Relative to the local population in their host country, immigrants in Canada do not do better than immigrants in other Anglo-democracies in their attention to politics in the media. This finding makes the previous question even more salient: why are immigrants in Canada relatively more interested in politics when compared to the local population than are immigrants in other Anglo-democracies?

Note:

The opinions expressed are those of the authors; they do not necessarily reflect those of the Chief Electoral Officer of Canada.