Retrospective Report on the 42nd General Election of October 19, 2015

4. Electoral Operations

This section provides behind-the-scenes perspectives on notable electoral administration activities. It looks at the challenges of administering one of Canada's largest civic exercises and summarizes what Elections Canada heard from election workers, returning officers and field liaison officers.

4.1. Challenges of a 78-Day Election Calendar

Key Findings

- The establishment of a fixed election date for 2015 did not provide as much predictability as anticipated for administering the election, given that the start date was not established in advance.

- While Elections Canada demonstrated agility and responsiveness after the election was called, there were some delays in deploying field operations, especially because of the need to renegotiate office leases and recruit election workers for an extended election period.

Context

Under Canada's parliamentary system, general elections are scheduled to take place on fixed dates but can still be called in advance. Election campaigns can also extend beyond the minimum 36-day period set out in the Canada Elections Act, with no maximum duration. The 42nd general election calendar was 78 days, making it the longest in 140 years.

Opening local offices

With the election date fixed for October 19, 2015, Elections Canada had selected September 1 as the date to begin deploying its field operations. Based on a 36-day election calendar, this would have provided a two-week head start for returning officers across the country to finalize temporary office leases, make arrangements for telephone and computer services, order election materials and begin to hire local office staff. This launch date was also used to plan the delivery date for support services, such as the start-up of call centres.

Elections Canada is informed about the start of general elections at the same time as all Canadians. When the election was called on August 2, 2015, the agency had to review its planning and immediately deploy its field operations. Returning officers had to renegotiate the start date of many leases, while 107 returning officers had to find a new office location. Returning officers also stepped up measures to engage local office staff earlier and for a longer period, and revised all planned deliveries of equipment and election supplies.

In the 42nd general election, 320 of the 338 returning offices (about 95 percent) were open and operational within eight days. The last returning office was opened and fully operational on August 18, which was 15 days after the election call; and the last satellite office was opened on August 19, which was 16 days after the election call. In the 41st general election, all local Elections Canada offices were considered operational within three days of the election call.

Some delays were experienced with specific support services. There is no doubt that, for the first few days of the campaign, some electors and political entities did not get the level of service they had been accustomed to in previous elections. The duration of the election period will be further discussed in the forthcoming recommendations report to Parliament.

The increased availability of online services may have minimized the impact of delays in office openings for electors. They were able to obtain information from the agency website, register online or apply electronically to vote by mail. For the 43rd general election, the agency will explore providing similar services to candidates.

4.2. Election Workers

Key Findings

- Some 285,000 election workers were hired across the country in 2015, compared with 229,000 in 2011 and 194,000 in 2008.

- The significant increase in workers required to deliver the election in the field indicates a need to seriously consider alternative operational models that can sustain and enhance the consistency and quality of services in the future.

- The process by which political parties may recommend election workers delays returning officers' recruitment efforts and only manages to fill a portion of the available positions.

- Overall, election workers felt that they were well trained and prepared to assume their tasks. They were satisfied with the materials and tools provided; however, some experienced difficulties with the functionality of these tools.

- Most election officers were satisfied with the operation of their polling place, including voter identification and the voting process. Some experienced challenges with revision procedures.

- While election officers qualified their working conditions as good, there are areas for improvement. They include better training, less paperwork, more work breaks, more staff, as well as better and more spacious facilities and locations.

Context

During a general election, returning officers in each of Canada's 338 electoral districts hire and appoint election workers–Canadians with limited training and often no prior electoral work experience–to administer the prescribed voting procedures at some 70,000 polling stations.

Elections Canada compiles data on staffing for each election. It also commissioned a survey of election officers to obtain feedback on their experience of the election. This section provides a summary of the findings for recruitment and proceedings at the polls.

Recruitment

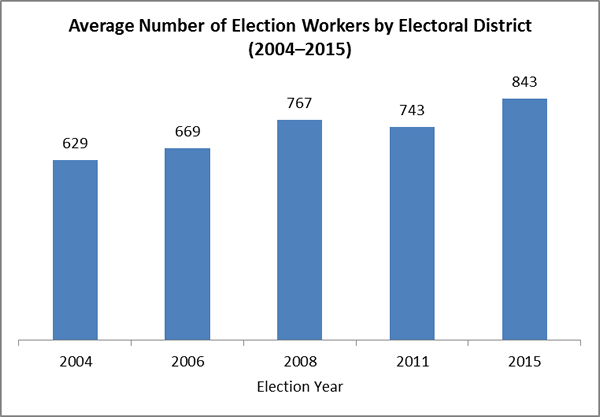

Some 285,000 people were hired to fill election worker positions in the 42nd general election, resulting in an average of 843 workers per electoral district. Returning officers hired around 55,000 more election workers in 2015 than in 2011, as shown in the graph below. This increase is mainly due to the additional personnel required to provide adequate services at the polls, maintain compliance with voting day procedures and meet accessibility requirements. The addition of 30 new electoral districts to accommodate the growth of the electoral population was also a contributing factor.

Text version of graph "Average Number of Election Workers by Electoral District (2004–2015)"

To fill these positions, returning officers must first turn to names provided by the registered political parties of the candidates who finished first and second in the electoral district in the last general election. However, this has become a decreasing source of potential workers, as the number of names submitted has declined over the past few elections. The proportion of poll workers recommended by candidates fell from 42 percent in 2006 to 33 percent in 2008, to 30 percent in 2011 and to some 20 percent in 2015.Footnote 23 Also, candidates provided such references in only 49 percent of electoral districts in 2015.

Recruitment has become more and more challenging. It is increasingly difficult to find enough people willing to accept the positions. Elections Canada took a number of measures to help returning officers in their recruitment efforts.

For the second time in a general election, any interested Canadian could fill out an online application to work at the polls. A total of 243,934 online applications were submitted to returning officers, compared to 130,427 in 2011.

To further ease recruitment, the Chief Electoral Officer authorized returning officers to hire 16- and 17-year-olds. It was suggested that they engage schools and school boards late in the spring, well in advance of the election. The results were very encouraging. In some cases, this work experience formed part of students' curricula.

Returning officers also recruited poll workers through targeted digital ads posted on employment-related websites; through job posters displayed in libraries, community centres and shopping malls; and by reaching out to community groups and local organizations to promote employment on voting days.

Finally, to supplement these efforts, Elections Canada enlisted the help of its regional media advisors across the country to conduct recruitment drives in some 60 electoral districts.

Training and support

Elections Canada's renewed training program included three-hour in-person training sessions for most workers across the country, and new online modules for select central poll supervisors and select election officers in remote areas.

Almost all election officers (96 percent) felt well prepared to undertake their tasks, according to the Survey of Election Officers. This is a significant increase from 89 percent in 2011. Almost all (97 percent) also felt prepared to apply the voter identification requirements. Likewise, 92 percent felt that they were well prepared to provide services to electors with disabilities.

The majority of election officers (84 percent) were satisfied with the training sessions, consistent with 83 percent in 2011 and 86 percent in 2008. Of those who were not satisfied with the training, suggestions for improvement included better quality training (41 percent), more time for training (23 percent), more detailed information (20 percent), more knowledgeable trainers (19 percent) and more hands-on training (17 percent).

The vast majority of election officers (95 percent) found their main guidebook useful. Most (89 percent) were satisfied with the election materials that were provided to them, compared to 90 percent in 2011 and 89 percent in 2008. Some 85 percent said the various forms that were provided to them were easy to complete.

Working conditions at the polls

Various media reported that poll workers experienced difficult working conditions. These conditions result in part from rules in the Canada Elections Act. For example, a deputy returning officer or poll clerk cannot be replaced by other election workers while the polls are open, which may limit breaks during busy periods. In some cases, especially where there were lineups or high turnout, workers faced 14- to 16-hour days. Difficult working conditions have been a source of concern for the Chief Electoral Officer, and he has raised the issue previously in reports to Parliament.

Nevertheless, almost all election officers (94 percent) found that their working conditions were good. Of the 5 percent who claimed working conditions were not good, the most common reasons were the lack of breaks (29 percent), inadequacy of the work place (22 percent), long working hours (22 percent) and the complexity of handling unique cases (17 percent).

A majority (87 percent) reported that the building where they worked was suitable for holding an election, compared to 89 percent in 2011 and 86 percent in 2008. Among those who did not find their building suitable, the top reasons were a lack of room (36 percent), inadequate heating (29 percent), and a lack of accessibility for people with disabilities (18 percent).

Prior to the 42nd general election, the tariff of fees for election workers was updated to provide higher wages. About four in five election officers (81 percent) were satisfied with their hourly rate of pay, compared to 78 percent in 2011 and 81 percent in 2008. Likewise, 86 percent were satisfied with the time it took to receive their pay cheque, which is a marked decrease when compared to 96 percent in 2011 and 2008. While still meeting its four-week service standard, Elections Canada required more time to pay poll workers in 2015 than in previous general elections. The exceptional duration of the event (78 days) and the growth in the number of poll workers increased the volume and complexity of pay transactions. The agency has already initiated a project to improve its performance in the next general election.

When asked about the first thing they would change to make their work easier at the polls, 74 percent of election officers proposed ideas. The top five suggestions were better training (17 percent), less paperwork (8 percent), having breaks (6 percent), more staff or help (5 percent), and a better or more spacious facility or location (5 percent).

Voter registration and the voting process

Most election officers (90 percent) were satisfied with the way the election went at their polling place, compared to 93 percent in 2011 and 89 percent in 2008. Overall, 93 percent reported that the flow of electors went smoothly, compared with 95 percent in 2011 and 94 percent in 2008. It can be noted, however, that this proportion was higher among those who worked on election day only (95 percent), and lower among those who worked at both advance polls and on election day (89 percent).

The vast majority of election officers (97 percent) indicated that voter identification proceeded well. This is similar to the 2011 and 2008 levels. Where problems did occur, the most common were electors showing up at the polling station without the proper identification, and electors thinking they could use their voter information card as a piece of identification to register or vote.

Most registration officers (86 percent) found it easy to register electors at the polls.

4.3. Voting Service Interruptions on First Nations Reserves

Key Findings

- Five out of 14 polling places experienced a voting service interruption on election day due to ballot shortages, resulting in 13 electors, all at one polling place, being unable to vote.

- These service disruptions, however regrettable, were isolated cases. Elections Canada sincerely regrets that these electors could not exercise their franchise.

- Elections Canada will work toward mitigating the factors that make planning voting operations on First Nations reserves more challenging.

During the 42nd general election, there were reports of voting service interruptions due to ballot shortages in a number of polling places on First Nations reserves. Despite immediate instructions from the Chief Electoral Officer to have ballots reallocated from neighbouring polling places or photocopied, there were reports of voters leaving their polling place without being able to vote.

In the weeks following the election, Elections Canada conducted an administrative review into these incidents, assembling facts from media reports as well as gathering eye-witness testimonies from returning officers, polling place supervisors, representatives of the Assembly of First Nations and local representatives of candidates' campaigns.

The review found that 14 polling places in nine electoral districts ran low on ballots on election day. In nine of these polling places, voting was not interrupted, as election officers were able to replenish the ballot supply before it was completely exhausted, either by reallocating ballots from another polling place or from the returning office. In some cases, they used photocopied ballots, as per instructions from the Chief Electoral Officer. In three First Nations communitiesFootnote 24, the issue was resolved within 10 to 12 minutes, while in One Arrow (Saskatchewan), service was interrupted for up to 30 minutes. Nevertheless, there were no eye-witness accounts of electors leaving the polling place without voting in these locations.

In an isolated incident, one polling place in Lake St. Martin (Manitoba) ran out of ballots before the close of polls. Election officers were uncomfortable with using photocopied ballots and refused to offer them to voters. As a result, 13 electors were unable to vote. Elections Canada sincerely regrets that these electors could not exercise their franchise.

The administrative review identified some contributing factors to the ballot shortages and service delays. These factors are relatively common in remote communities of large rural electoral districts, where many First Nations reserves are located. For example, voter registration drives in remote communities are more difficult to conduct and less effective. As well, Elections Canada's online voter registration service was unable to handle the non-standard address types found on many First Nations reserves. The result was low registration rates during the revision period and, given the sharp turnout increases, much higher registration rates on election day.

With turnout on First Nations reserves now approaching that of the general population, this is an important consideration, particularly because registrations during the revision period are used to forecast the volume of ballots needed at a polling station. If advance registration is low, the actual number of ballots required in a community may be underestimated. Returning officers will take this into account to improve their planning for the next general election.

4.4. Feedback from the Field

Key Findings

- Field administrators had a number of wide-ranging recommendations for improving the conduct of elections at the local level.

- Elections Canada needs to continue engaging returning officers and field liaison officers as it reviews and responds to their concerns and suggestions.

Context

In January and February 2016, officials from Elections Canada held regional meetings with returning officers and field liaison officers to gather their feedback about field operations in the 42nd general election. With over 300 participants, 27 days spent in the regions and 70 returning officer workbooks available for review, Elections Canada officials were able to gain a genuine understanding of returning officers' experiences and their ideas about improving field operations. This section provides an overview of some of the feedback received.

Summary of the regional meetings

The main recommendations from returning and field liaison officers who participated in post-election regional meetings focused on improving the working relationship between Elections Canada and the field. They suggested enhancing Elections Canada's support by assigning more experienced personnel to interact with them. They also emphasized the importance of simplifying and better coordinating communications and information flows between the agency and the field.

A number of suggestions were made to improve and streamline services for electors. These included rethinking the current polling division model to enable more flexibility for electors to vote where they want, especially during advance polls. Other suggestions included simplifying the advance voting process and holding election day on a weekend, when more people are available to work and vote. To make poll worker recruitment easier, participants suggested beginning recruitment before the election call.

Returning officers expressed a need for enhanced technology both in their offices and at the polls. Their vision of modern election services includes the automation of poll procedures and the availability of live voters lists at the polls to speed up the administration of the election. They also indicated a need to further automate and integrate some processes, such as recruitment and pay for election workers, and to streamline other processes.

With regard to the competency of election officers, returning officers recommended simplified, more hands-on and practical training as well as simplified election materials to help improve compliance with procedures. They also mentioned that the legal framework within which election officers operate is very complex and cumbersome, and should be streamlined.

Finally, returning officers saw potential benefits in re-examining advance polling districts and polling divisions after an election, and called for a reduction in the number of electors per advance poll.

4.5. Conclusion and Next Steps

The establishment of a fixed election date did not fully produce the hoped-for predictability for administering the 42nd general election. The absence of a fixed start date, or a specified time range within which to conduct the election, resulted in significant deployment challenges and delays. These delays, in turn, inconvenienced some electors and political entities. Elections Canada will make recommendations in its upcoming report to better define the duration of an election period.

In 2015, returning officers hired around 55,000 more poll workers than in 2011. While the addition of 30 new electoral districts accounted for part of this increase, the significant expansion of the workforce was mainly to provide adequate services at the polls, maintain compliance with procedures and meet accessibility requirements. Continuing to rely primarily on increased staffing to improve and ensure the quality of voting services is not sustainable. There is a pressing need to streamline and automate services at the polls, as well as to explore more efficient ways of allocating human resources at polling places. As part of its voting services modernization efforts, Elections Canada will work to revamp services at the polls for the 43rd general election. It will also make recommendations to Parliament on this subject in its upcoming report.

To recruit poll workers, returning officers must first turn to the names provided by political parties. Over the years, these references have become a diminishing source of potential workers. Effective election services in the field require that returning officers recruit, hire and train a sufficient number of qualified workers in a timely manner. Elections Canada will make recommendations in its upcoming report to Parliament to ensure that returning officers are equipped with the staff that they need, when they need them.

As part of its modernization efforts, Elections Canada will undertake a multi-tier approach to improving the poll worker recruitment process. This will include legislative recommendations to alleviate unnecessary burdens or eliminate outdated milestones for recruitment, enabling returning officers to recruit workers through streamlined and automated processes and to target young workers through early outreach efforts.

With respect to voting operations on First Nations reserves, where ballot supply issues affected a few communities, Elections Canada will work toward mitigating the factors that make planning voting operations in large rural electoral districts more challenging. First, the agency will work to improve voter registration services and to increase the currency of the voters lists on First Nations reserves. This will start with a re-examination of how the online voter registration service handles electors' addresses, with a view to enlarging the scope and variety of its address standards. Second, additional information and training programs are warranted for returning officers and election workers who provide election services in remote communities, given the specific challenges in those regions. It is also important to reach out and work with the community in preparing to conduct the election.

As part of its modernization efforts, Elections Canada will continue to work with returning officers to improve the management of field operations. It will strengthen the communications, coordination and support functions between the field and headquarters. It will continue to provide online training that is practical, hands-on and targeted at providing election workers with the knowledge and skills that they need to perform their specific tasks.

While almost all election officers found that their working conditions were good, Elections Canada believes there is room and a need for improvement. There is a fundamental imbalance between the growing job demands on election workers and the challenging conditions in which they are met. The integrity of the electoral process depends on the ability to attract, motivate and retain large numbers of appropriately skilled Canadians. They must be willing to accept election work and perform assigned duties diligently, for one day or a few days. Elections Canada will seek to provide a greater opportunity for breaks, allow workers to be replaced for short periods of time, and establish a rotation of workers to better respond to lineups and delays. Elections Canada will make recommendations to Parliament on these issues in its upcoming report.

Return to source of Footnote 23 Based on a sample of electoral districts.

Return to source of Footnote 24 These were the First Nations communities of Siksika (Alberta), Fort Hope (Ontario) and Moose Factory (Ontario).