A Comparative Assessment of Electronic Voting

Part VI: General Considerations for Canada

As noted above, while we can learn from the experience of others, a Canadian application of remote Internet voting must take account of specific features of the Canadian context. This section identifies some of factors that might be considered in the development of a Canadian model.

The Trade-off Between Accessibility and Security

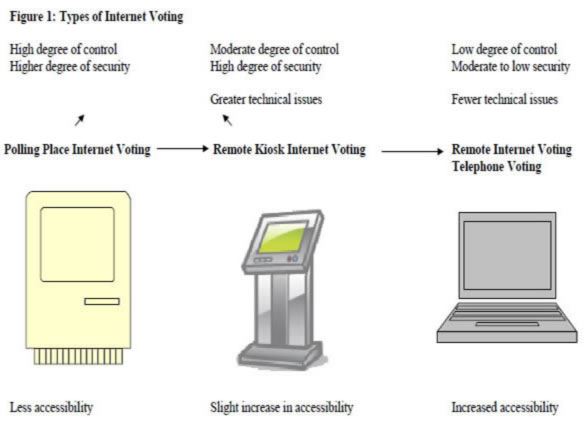

Though remote voting has the highest potential to enhance accessibility and encourage participation, it also gives election officials the lowest amount of control over the process. In selecting a voting method, it is useful to evaluate the types of Internet voting in the model below (Figure 1). For the most part, as election officials sacrifice direct control over the voting process access is enhanced. However, a loss of direct control need not imply an unacceptable increase in security risks. Practical cases have shown that more technical difficulties appear to be associated with Internet voting machines located in polling places or Internet kiosks than with remote Internet voting. The decision to pursue remote Internet voting does hold promise to yield the greatest benefit to electors in terms of increasing access while minimizing security risks, assuming adequate protective measures are put in place. However, these benefits must be weighed against the effect of reduced control on election administration and the electoral process more generally.

Text description of Figure 1 is available on a separate page.

Access

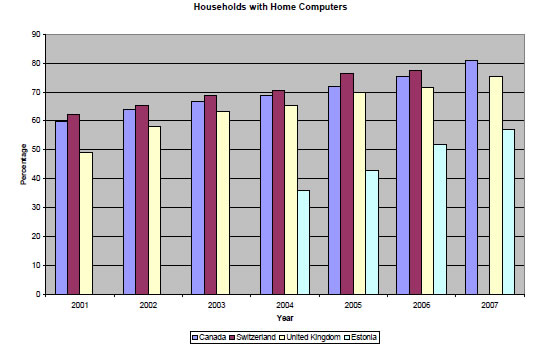

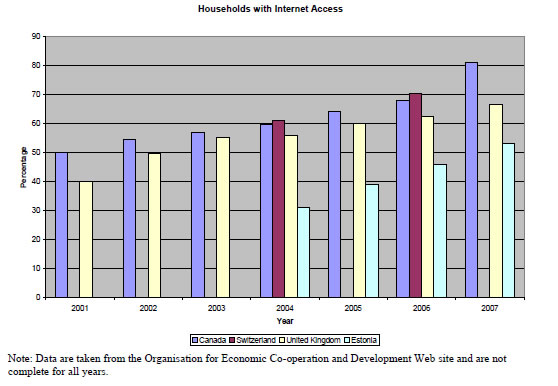

While a key goal of remote Internet voting is to improve access, it depends on a substantial proportion of the population having computers and Internet connectivity. In the remote Internet voting projects discussed above, the governments instituting the programs believed that the rates of access in their areas were high enough to successfully proceed (though Halifax chose to also offer telephone voting). Comparative data suggests that Canada, overall, compares well with other countries in terms of Internet access47. The number of households with personal computers and Internet connectivity in Canada is actually higher than the European countries examined here.

However, Internet access may be unevenly distributed in various parts of the country. Rural areas, the North, and other regions may have reduced access. The size and diversity of the country might suggest a diversified approach, where traditional balloting methods, kiosk voting or telephone voting may be more appropriate in areas where Internet access is less widespread. In addition, trials of various methods would need to take account of this factor.

Figure 2: Households with Home Computers

Text description of Figure 2 is available on a separate page.

Figure 3: Households with Internet Access

Text description of Figure 3 is available on a separate page.

Turnout

The potential impact of electronic voting on voter turnout has been an important reason for considering such a system in the European and Canadian municipalities that have implemented pilot projects. While it is difficult to generalize from these examples, in all Canadian municipal trials conducted thus far, turnout increased in whichever part of the election electronic services were offered. For example, in the cases of Markham and Peterborough, although remote Internet voting was only offered during advance polling, turnout in those polls registered strong increases from past elections that relied solely on paper ballots. Halifax, Markham, Estonia and Geneva all noted significant increases in the second official ballot where remote Internet voting was an option. And, with respect to Estonia and Geneva (the only cases that offered remote Internet voting in three elections), turnout climbed again in the third contest. It does appear, therefore, that where remote Internet voting is offered, increasing numbers of people use that method over time. It is still unclear, however, whether this results in an overall turnout increase.

Cost

Cost is an important consideration in election administration. Methods of electronic voting may be more costly in the initial stages than traditional paper ballots, but many of the companies responsible for running electronic elections claim they have the potential to save the jurisdictions that use their services a large amount of money over the longer term. In Canada, for example, the 2008 federal election cost approximately ten dollars48 per eligible voter. This money covered expenses relating to the printing of ballots, staffing the polling stations and other general costs associated with running the election. Typically a provincial election can cost anywhere from seven to nine dollars per eligible voter, whereas municipal elections range from four to six dollars. While kiosk Internet voting and polling place Internet voting machines can be very cost-intensive to initiate, maintain and store, the cost to conduct remote Internet and telephone voting is substantially lower. Though exact prices differ based on the service provider, the standard rate worldwide is approximately two dollars49 per elector plus the cost of the mailer or any voter cards that the electoral agency mails out with PINs and other essential information. This cost includes the general operation of an electronic election (services like a call centre for electors to phone if they have questions, a scrutineer system for candidates' representatives, and all other protocols required by election officials) (Smith, August 26, 2009).

Initially, these electronic election costs would be in addition to the normal cost of the paper ballot process currently employed. In addition, advertising expenses would be required to familiarize the public with the operation of the electronic system. Over time, however, as use of the electronic election methods increased, costs associated with the regular election process could be reduced, rendering the ultimate situation more cost-neutral. Reliable cost estimates are impossible to make in advance.

Legal implications

At the local level in Canada, municipalities are able to pass by-laws that allow for the use of alternative voting methods. If there is any conflict between a by-law and the existing legislation, the by-law supersedes anything contradictory in the legislation. At the federal or provincial levels, since there is no by-law option, the government must grant the chief electoral officers the power to try different forms or methods of voting. At the federal level, for instance, section 18.1 of the Canada Elections Act (introduced by Bill C-2 and assented on May 31, 2000) authorizes the Chief Electoral Officer to carry out studies and tests on alternative voting means, including electronic voting processes. However, prior to the implementation of such a process in an official vote, it is required that the proposed method or system be approved by House of Commons and Senate committees.

In addition to the approval of parliamentarians, the introduction of electronic voting may require the passage of legislation or an amendment to the Act allowing for the use of alternative voting methods, especially if the methods were to become a permanent fixture in the electoral process. The wording could be more open, allowing for multiple alternative voting methods, or could specify the exact methods to be used such as remote Internet and telephone voting. This would depend on whether Parliament wanted to be able to approve any specific methods that may be proposed for use in the future. Official approval of electronic voting would have to be accompanied by an election policies and procedures document that would establish the rules and guidelines outlining various components of the election. Three items that must be outlined in this document include the form of a ballot,50 a mechanism to count the ballots and a process to contest a ballot (Smith, August 26, 2009). Other items could cover issues pertaining to authority, definitions, secrecy, voters lists, voter qualifications, the voting process, the electronic voting system, candidates' representatives, results, recount procedures, emergencies, financial disclosure for candidates and various other aspects of the election process (Intelivote, 2009).

Implications of the federal structure

European experience indicates that a step-by-step approach, involving introduction of only one or two Internet options at a time, in a well-designed program, increases the likelihood of success. If federal, provincial and municipal election offices simultaneously introduce their own mix of Internet or remote voting options, using different approaches and technologies, this may result in voter confusion. An open consultative process between various jurisdictions within Canada would be important to reduce the likelihood of such a situation.

Software

When selecting a type of Internet voting software, there are two options: proprietary and open-source. The central distinction between the two relates to ownership and intellectual property. Proprietary software is owned by the company that provides it, unless otherwise stipulated, and can only be used based on licensing conditions. Open source software by comparison still has a software licence, but the licence exists to protect the freedom of the software and the users (Gallagher, October 2, 2009).

All Internet voting projects to date, with the exception of the Australian Capital Territory project, have used proprietary software. Geneva, in particular, hotly debated the issue and then held a referendum concerning which type of software it was going to use. In the end, it decided that proprietary software would instil greater public confidence in the on-line voting process. Interestingly, although the USA has yet to trial remote Internet voting, many prominent American scholars (particularly Alvarez and Hall, 2004 and 2008) are proponents of open-source software. One of the major criticisms of the kiosk Internet voting project in Ireland was the lack of transparency with respect to the source code because it was not open-source. In the future consideration of electronic voting methods, the Commission on Electronic Voting recommended that only open-source software be considered for use (Interim Report of the Commission on Electronic Voting, 2006). Given these conflicting opinions, it is important that Canadian electoral agencies be informed of and carefully considers both types of software prior to developing a model for the conduct of elections.

In Canadian local elections, no municipalities chose to use an open-source software provider for the electronic portion of their elections because of convenience and small or non-existent research budgets. In addition, there are no Canadian companies that offer open-source election programs, so it is easier and more convenient for municipalities to select a company that not only has a program, but has also implemented it in official votes in other jurisdictions.

There are several important benefits associated with an open-source software product. For one, the source code (the language the computer program is written in) is open. That means it is transparent and can be peer-reviewed by anyone, anywhere. It is a common misconception that closed-source software is more secure than an open-source product because it is assumed that security is created by obscurity instead of by design (Gallagher, October 2, 2009). The development of Internet voting machines using open-source code in the Australian Capital Territory is a practical example of the benefit of the transparency open-source software provides. A local academic identified a mistake in the code that, although not a functional or security error, was a serious flaw nonetheless. Were it not for the code being open to public scrutiny, this flaw may not have been detected (Zetter, 2003). While some proprietary companies will allow their software to be peer-reviewed, provided the reviewing party signs a non-disclosure agreement, this is not always the case.

Furthermore, with proprietary software, a fee must be paid for every use and the software provider is relied upon for updates. This is not the case with open-source software, since the copyright could be owned by the purchaser. Open-source software products also allow for a greater role in product development and degree of control in verifying the development of desired software elements (Gallagher, October 2, 2009). Finally, the open nature of the code allows the model to be copied and used by others. While no one else is able to change the framework, if an open-source Internet voting model is used in Canada, there would be the potential for other governments to refer to it as an 'ideal type' for Internet voting. In this sense, the open-source software could provide an opportunity for others to follow and learn directly from the Canadian experience.

Other effects on the electoral process

The emergence of Internet voting in Canada would not only impact electors' choices and the way they vote, but also other aspects of the electoral process, notably the nature of campaigning. The implementation and popularity of Internet voting would have a significant effect on the campaign and the predictability of elections as well as on how candidates and parties mobilize voters. In Markham, for instance, one notable comment from officials was that on-line voting altered the landscape of how candidates needed to campaign. While canvassing, candidates encountered many electors who had already voted. A greater number of electors voting in the advance polls because of Internet convenience meant there were fewer votes to mobilize on election day. In addition, in Halifax, candidates were able to keep track of supporters during campaign timelines using an Internet candidate module. This allowed for the generation of multiple support lists such as a special list of undecided voters or categorization by area (i.e. street), which was a useful vehicle for mobilization. It also reduced the need for the traditional candidates' representative function because parties were able to track participation on-line. Though these are only some examples, there are many other potential effects that the extension of Internet voting could have on the campaign process, particularly voter mobilization.

Steps Needed to Achieve Internet Voting in Canada

Many of the steps needed to achieve Internet voting in Canada have been outlined throughout the report. The following eight steps can be identified in particular, although they would not be required to occur sequentially.

First, ensuring access is essential. This includes making sure that an adequate number of households have computers with access to the Internet, while taking account of differences between constituencies. Ensuring equality of access may require the inclusion of additional public Internet voting sites or making other voting methods more accessible in areas of lower income or rural areas where connectivity may be an issue.

Second, a culture of support – from government, the election administration body, political parties and candidates as well as electors – is required. To allow for a smooth introduction, it is important that all parties affected by the change are generally supportive, and that concerns are addressed.

Third, there is a need for a legal framework that supports the use and implementation of alternative electronic voting methods. In most cases, Canadian trials will require approval of the specific method by parliamentarians, and likely additional legislation if the method is to become a permanent fixture of the Canadian electoral process.

Fourth, thorough research and an assessment of trials and tests in other jurisdictions as well as an analysis of their outcomes is essential. It will be helpful to pursue the cases discussed in this report to identify particular features of superior approaches that may be useful in developing a given model for Canada.

Fifth, it is important that there be a clear picture of the benchmarks and requirements an additional voting method would be expected to fulfill, as this will provide a framework for distinguishing which electronic or Internet voting method is a good fit for the Canadian electoral process.

Sixth, a marketing and information campaign appears to be an important step toward not only launching, but also maintaining a successful Internet voting program. In addition to informing electors of the choice of alternate voting methods, information concerning the importance of voting or other details regarding candidates or their platforms could be included.

Seventh, gradual, practical testing appears to be a necessary step. Gradual trials would involve introducing Internet voting in sequential electoral races whereby the number of voters affected would increase with each pilot as well as the perceived importance of the election.

Finally, adequate evaluation of pilots is recommended to ensure the method is meeting desired objectives, and that all stakeholders are satisfied with the change and its consequences. This would involve conducting surveys among political parties, candidates, election administrators and electors.

47 Please note that the Canadian percentages for 2007 are actually based on the 2008 figures because no 2007 data were available. The 2008 data were obtained from the Survey of Electors Following the 40th General Election.

48 The cost was actually $13 per eligible elector, but the remaining $3 per elector goes toward paying back the political parties for their campaigning costs (Smith, August 26, 2009).

49 This cost is based on remote Internet and telephone voting and not the electronic machines.

50 The form of a ballot is what the ballot actually looks like, i.e. the order in which the candidates are arranged on the ballot and so on.