Chapter 4 – A History of the Vote in Canada

Advancing Fairness, Transparency and Integrity, 1982–2020

Back to Table of contents, Chapter 4

The history of the franchise took a new turn in 1982, when the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms was adopted as part of the Constitution. The Charter protects basic rights and freedoms, including the rights to vote and to become a candidate. Its adoption led to court challenges of certain provisions of the Canada Elections Act and the extension of voting rights to previously excluded groups–judges, prisoners, expatriates and certain people with mental disabilities. Other court challenges under the Charter involved certain restrictions on political parties and other groups.

Although legal restrictions were lifted for many people, additional barriers to voting remained for some. Further legislative and administrative reforms have sought to make the process of casting a ballot more accessible to people with disabilities. Likewise, the extension of periods for advance voting and the introduction of special ballots provided additional opportunities for all Canadians to vote.

Legislative and administrative measures were also introduced to help ensure that everyone has an equal opportunity to participate and to strengthen the integrity of the voting process. For instance, the Canada Elections Act was amended to require voters to prove their identity and address before casting their ballot. Elections Canada also took measures to address fairness in the administration of elections. As well, instead of being appointed by the government, returning officers would now be appointed by the Chief Electoral Officer based on merit.

Meanwhile, the regulation of political financing was extended with the aim of making it fairer and more transparent. Contributions from corporations and trade unions were first limited and then banned. Rules were also imposed on spending by other so-called third parties–persons or groups other than candidates and political parties. These and other measures have resulted in Elections Canada taking on a more complex role.

Although the regulation of third-party spending was challenged under the Charter, the courts ruled that broad regulation of electoral spending, while limiting the freedom of expression, is justified in the name of electoral fairness. The courts also affirmed the need to ensure the representation of communities of interest when establishing electoral boundaries.

This chapter reviews the changes that resulted from the adoption of the Charter and looks at the other legislative and administrative reforms that were put in place between 1982 and 2020.

The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms

One of the most significant influences on electoral law in the postwar years was the adoption of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, most of which came into effect on April 17, 1982. The Charter ensures fundamental freedoms–such as freedom of religion, opinion, expression and association–subject only to such reasonable limits prescribed by law as can be demonstrably justified in a free and democratic society.

No previous constitutional document had entrenched the right to vote, but section 3 of the Charter specifically deals with democratic rights. It states that every citizen of Canada has the right to vote in an election of members of the House of Commons or of a legislative assembly [of a province or territory] and to be qualified for membership therein.

Unlike some sections of the Charter, section 3 cannot be overridden by the federal Parliament or provincial or territorial legislatures using the so-called notwithstanding clause.footnote 1

Also, sections 4 and 5 guarantee that there shall be a session of the Parliament of Canada and of each provincial or territorial legislature at least once every 12 months. These sections add that no House of Commons and no legislative assembly shall continue for more than five years. Exceptions are times of real or apprehended war, invasion or insurrection. In such cases, the term of the House of Commons or of a provincial or territorial legislative assembly can continue as long as the continuation is not opposed by the votes of more than one third of the members.

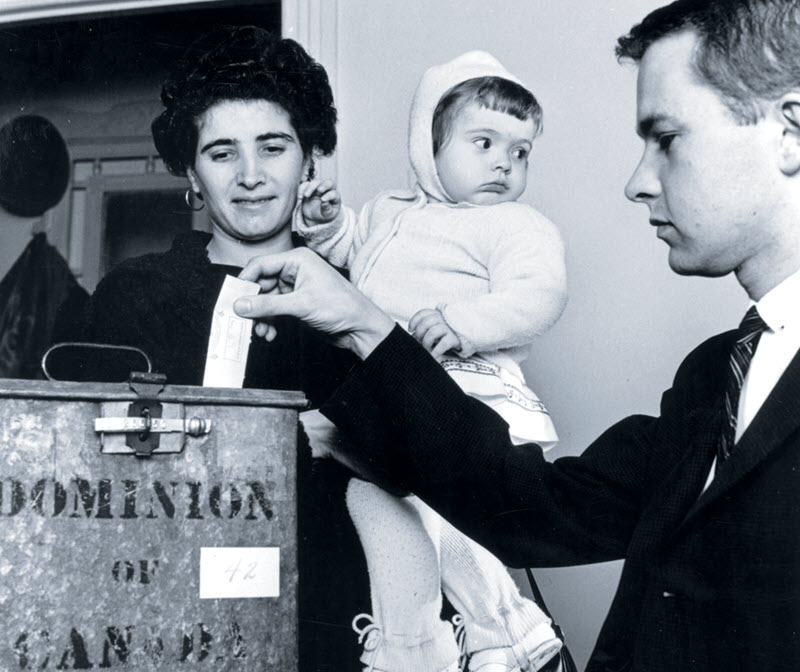

A Democratic Right

The rights to vote and to be a candidate for office have been enshrined since 1982 in the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, which is part of the Constitution Act, 1982. The Charter provided a basis for several groups to challenge their exclusion from the franchise and to contest other election law provisions in the courts. Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II signed the Proclamation of the Constitution Act, 1982, at a rainy ceremony on Parliament Hill on April 17, 1982. Library and Archives Canada e002852801

Well before 1982, many Canadians probably assumed that their right to vote was assured. As we have seen, however, many people had been denied the franchise–some on racial or religious grounds and others because they could not get to a poll on voting day. Even when improvements were proposed that would make it easier to access polls and to vote–such as extending advance polling to groups other than railway workers and commercial travellers–these measures sometimes provoked resistance in Parliament. For example, it took 50 years to extend advance voting to everyone who wanted it; each time a new group was given the privilege

of advance voting, there was opposition, generally based on cost or administrative convenience. Arguments based on democratic rights and principles were heard less often.

The Charter signalled a new approach. Canadians can use the Charter to challenge losses or infringements of rights. Someone who is denied the right to vote by a federal or provincial statute, for example, can bring a claim before the courts. If the case is successful, the courts might strike down part of the law or require changes in the administrative rules that resulted in disenfranchisement–which has happened frequently since 1982.

Significant advances in election law and administration occurred before the Charter. For instance, denial of the right to vote on the basis of gender, religion, race, ethnicity and income had been removed from the law, and administrative steps had been taken to improve access to the vote for people with disabilities, people away from home on election day, and members of the public service and the military serving abroad. The Charter ensures that these rights are constitutionally protected.

Also, there was mounting interest in addressing public perceptions of undue influence, as the financial activities of political parties and third parties were essentially unregulated. Yet the efforts to do so–by adding restrictions on electoral financing to the Canada Elections Act–also fuelled numerous Charter challenges. Alleged infringements of freedom of expression–guaranteed under section 2(b) of the Charter–were the most commonly cited cause for legal recourse. Restrictions on broadcasting, third-party advertising and the publication of election surveys during election campaigns faced similar tests under the section 2(b) guarantee.

Many of these problems have been addressed. Measures that Parliament and election officials have taken ensure that Canada's electoral process is both legally and administratively consistent with Charter principles. This makes the vote accessible to everyone who is entitled to cast a ballot while protecting the integrity of the process: the influence of money on electoral contests is balanced with freedom of expression.

Indeed, the courts have embraced a vision of electoral democracy that allows for a regulated process and a fair amount of deference to Parliament. This is in contrast with the less restrictive approach taken by courts in the United States of America. For example, the Supreme Court of Canada has ruled that while regulations on spending by third parties limit their freedom of expression, these limits are justified in the name of electoral fairness. Canadian courts have also developed the concept of a right to effective representation. Under this concept, significant population variations between electoral districts are tolerated to allow for better representation of communities of interest.

Compliance with Charter principles was assisted by the Royal Commission on Electoral Reform and Party Financing (also known as the Lortie Commission after its chair, Pierre Lortie). It was appointed in 1989 by the Progressive Conservative government of Brian Mulroney to review, among other matters, the many anomalies in the electoral process that Charter challengers identified. In 1992, the House of Commons Special Committee on Electoral Reform (known as the Hawkes Committee after its chair, Jim Hawkes) reviewed the Commission's recommendations and produced additional ones. These recommendations led to the passage of Bill C-78, An Act to amend certain Acts with respect to persons with disabilities, in 1992 (discussed in the section of this chapter on accessibility of the vote) and Bill C-114, An Act to amend the Canada Elections Act, in 1993. Together, these bills initiated significant changes in the way electoral law dealt with access to the vote. Further changes were made to political financing in the early 2000s based on the Commission's recommendations.

Bill C-114, An Act To Amend The Canada Elections Act

Among its many wide-ranging amendments to the Canada Elections Act in 1993, Bill C-114:

- gave electors from both rural and urban areas the right to register to vote on election day

- extended the use of the special ballot, so any elector could register and vote without having to appear in person on election day or at an advance poll

- permitted any elector to vote at an advance poll

- removed voting disqualifications for judges, certain people with mental disabilities and inmates serving less than two years in correctional institutions

- imposed a limit on expenses incurred by third parties to support or oppose a registered party or candidate during an election

- banned political donations from foreign sources

The period also saw a major revision to the Canada Elections Act. The years between 1970 and 2000 saw an intimidating maze of updates, amendments, revisions and clarifications, to the point that the Act had become hard to decipher. Also, the 1992 reports of the Lortie Commission and the Special Committee on Electoral Reform, as well as related input from the Chief Electoral Officer, made it increasingly clear that the Act needed much more than a bit of housecleaning.

With the experience of the June 1997 general election still fresh, the House of Commons Standing Committee on Procedure and House Affairs tabled its own report the following June. Its synthesis of the previous work and recommendations made over the years provided the basis for the new legislation. With the passage of Bill C-2, Canada Elections Act, in September 2000, the previous Act was repealed. It was replaced with a new statute that streamlined the language of the provisions and the way they were organized.

The new Act also made significant changes: these included improving access to the ballot, regulating the publication of election surveys and regulating election advertising by third parties. Court decisions had struck down the 72-hour blackout period that had been introduced in 1993; the 2000 Canada Elections Act limited the blackout period to the transmission of election advertising on polling day, until the close of all polling stations in the electoral district. The Supreme Court of Canada upheld the new blackout provision, as well as the regulation of third-party advertising, in 2004 (Harper v. Canada (Attorney General), 2004 SCC 33).

The Act also contained important new provisions for enforcement.

Bill C-2: The 2000 Canada Elections Act

Here are some highlights from the new Act:

- Provisions were reorganized and clarified to make them easier to interpret and apply.

- Third-party registration and reporting requirements and spending limits of $150,000 nationally—$3,000 in a particular electoral district—per general election were created. (Spending limits are adjusted annually for inflation.) Spending limits also apply during by-elections, in which case they apply to spending within the electoral district.

- The publication or broadcasting of election advertising and new election survey results was prohibited on election day until all polling stations in the electoral district had closed.

- Disclosure of financial information by registered parties was subject to more rigorous reporting requirements.

- The Commissioner of Canada Elections was empowered to enter into compliance agreements and to seek injunctions during a campaign to require compliance with the Act.

The Right to Vote

The main beneficiaries of Charter challenges to electoral law, as far as the right to vote is concerned, have been judges, prisoners, people with disabilities, and Canadians living abroad.

Jean-Marc Hamel, the Chief Electoral Officer when the Charter was adopted, began the process of responding to the Charter's impact on the Canada Elections Act by identifying the provisions of the Act that were vulnerable to court challenges and should be changed. By the time Jean-Pierre Kingsley was appointed Chief Electoral Officer in 1990, a dozen or so cases had already come before the courts to challenge the Act on Charter grounds. He also made a series of recommendations for amending the Act.

Federally appointed judges had been legally disqualified from voting since 1874. The law remained in place until 1993, but a Charter ruling at the time of the 1988 general election rendered the provision inoperative. About 500 federally appointed judges became eligible to cast ballots in federal elections after a court struck down the relevant section of the Canada Elections Act, declaring it contrary to the Charter's guarantee of the right to vote.

Prisoners had not been allowed to vote since 1898–although according to at least one MP, Lucien Cannon, speaking during the 1920 debate on the Dominion Elections Act, some inmates appear to have found a way around the rules:

I know a case where the prisoners were allowed, under a sheriff's guard, to go and register their votes and they came back afterwards.

The solicitor general of the day appeared not to credit this story, replying that prisoners might be on voters lists, but since they could not get to a ballot box, they would be disenfranchised in any event.

Prior to 1982, there was little parliamentary support for ensuring that prisoners could exercise the right to vote. After 1982, however, inmates relied on the Charter to establish through the courts that they should indeed be able to vote. They began by challenging provincial election laws, where they had some success. Then, during the 1988 federal election, the Manitoba Court of Appeal ruled that it was up to legislators to determine which prisoners should or should not be enfranchised. In 1993, Parliament removed the disqualification for prisoners serving sentences of less than two years, but prisoners serving longer terms were still disqualified from voting.

The new provision was challenged by an inmate serving a longer sentence. In its decision in Sauvé v. Canada (Chief Electoral Officer) in 2002, the Supreme Court of Canada ruled that prisoners serving terms of two years or more could not be disqualified from voting, as doing so was an unreasonable limit on their right to vote. The Court's ruling secured access to the vote for all prisoners. Although the Canada Elections Act was not amended right away, the Chief Electoral Officer applied the decision during subsequent general elections. In 2018, the inoperative provision was repealed by Bill C-76, the Elections Modernization Act.

Denying the right to vote does not comply with the requirements […] that punishment must not be arbitrary and must serve a valid criminal law purpose. Absence of arbitrariness requires that punishment be tailored to the acts and circumstances of the individual offender.

The Courts and the Charter

The Supreme Court of Canada and several provincial courts, in interpreting the rights guaranteed in the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, have made a number of rulings on provisions of the Canada Elections Act. Court rulings have affected the definition of who has the right to vote, the number of candidates required for a political party to qualify for registration, limits on the publishing of election surveys during a campaign period and spending by third parties. Elections Canada

Prisoners and the Vote: Sauvé V. Canada

- 1992

-

Sauvé v. Canada challenged a long-standing provision in the Canada Elections Act that prohibited inmates from voting. In its decision, the Ontario Court of Appeal considered three objectives that might be deemed important enough to infringe on prisoners' right to vote:

- affirming and maintaining the sanctity of the franchise in our democracy

- preserving the integrity of the voting process

- sanctioning offenders

The Ontario Court of Appeal ruled that, even if taken collectively, these objectives could not justify outright denial of voting rights. The federal prohibition on inmate voting was repealed. The timing of the decision enabled inmates to vote during the 1992 federal referendum on the Charlottetown Accord.

- 1993

-

The Supreme Court of Canada upheld the Ontario Court of Appeal's decision, stating that the Act's prohibition against inmate voting was too broad: it failed to meet the requirement that penal sanctions must result in minimal impairment of Charter rights and that the negative effects of impairing the right must be proportionate to the benefits.

That same year, Bill C-114 removed the voting exclusion for prisoners serving less than two years.

- 1995

-

In Sauvé (1995), the Federal Court Trial Division accepted the government's argument that enhancing civic responsibility, respect for the law and the general purposes of penal sanctions were important enough objectives to warrant infringement of a Charter right. The Court found, however, that the disqualification for inmates serving two years or more still failed the requirements of both proportionality and minimum impairment. Successful administration of the inmate vote in the 1992 referendum also appears to have influenced the Court's decision to strike down the prisoner voting restrictions in Bill C-114.

- 1999

-

The Federal Court of Appeal reversed the Federal Court's ruling and upheld the voting disqualification for inmates serving two years.

- 2002

-

On appeal, the Supreme Court of Canada overturned the Federal Court of Appeal's decision, concluding that

- denying individuals the right to vote will not educate them in the values of community and democracy

- a blanket disenfranchisement is an inappropriate punishment because it is not related to the nature of the individual crime

- disenfranchisement does not increase respect for democracy because it denies individuals' inherent dignity.

- 2004

-

Parliament did not amend the Canada Elections Act right away to remove the voting disqualification for inmates serving two years or more. Nevertheless, the Chief Electoral Officer applied the Sauvé (2002) decision during subsequent general elections, giving all inmates the opportunity to vote.

- 2018

-

Bill C-76 repealed the provision in the Canada Elections Act that had disqualified federal inmates from voting and that the Supreme Court had struck down.

In the 1980s and early 1990s, several changes in election administration and the law made it much easier for electors with disabilities to vote. One group of people with disabilities remained explicitly disenfranchised under the Canada Elections Act, however–those who were restrained of [their] liberty of movement or deprived of the management of [their] property by reason of mental disease.

In 1985, a House of Commons committee recommended that they be enumerated and have the same right to vote as other Canadians. The 1992 report of the Lortie Commission said that the disqualifying of these electors clearly belongs to history.

In the meantime, the courts struck down the provision. In 1988, the Canadian Disability Rights Council, a coalition of disability rights groups, argued in a Charter challenge that the Canada Elections Act should not disqualify people who were under some form of restraint because of a mental disability. The Court agreed, although it did not specify what level of mental competence would qualify a voter. In 1993, Parliament removed disqualification on the basis of mental disability as part of Bill C-114.

The 1992 Referendum on the Charlottetown Accord

On October 26, 1992, the third federal referendum was held. The Charlottetown Accord, which had been negotiated by Prime Minister Brian Mulroney and the provincial premiers, would have amended the Constitution to cede several federal powers to the provinces, address the issue of Indigenous representation in Parliament, reform the Senate and recognize Quebec as a distinct society. Canadians were asked to vote yes

or no

to the question Do you agree that the Constitution of Canada should be renewed on the basis of the agreement reached on August 28, 1992?

Quebec conducted its own referendum on the same question.

The vote was held under the provisions of the Referendum Act, which was passed in June 1992. It provides for, among other things, the regulation of registered referendum committees and of contributions and expenses incurred to support or oppose the referendum question.

Voter turnout in all provinces and territories except Quebec was 71.8 percent. Voters rejected the Accord, with 54.3 percent voting no.

A case involving the right to vote arose from the 1992 referendum. A voter named Graham Haig had moved from Ontario to Quebec less than six months before the referendum took place and was therefore not qualified to vote in that referendum. He took the matter to court. In September 1993, the Supreme Court of Canada ruled that his exclusion from the federal referendum had not violated his rights under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. While section 3 of the Charter applies to the right to vote in federal and provincial elections, it does not apply to voting in a referendum (Haig v. Canada (Chief Electoral Officer), [1993] 2 SCR 995).

Requirements for voters to provide proof of identity and address were introduced by Bill C-18, An Act to amend the Canada Elections Act (verification of residence), in 2007. These requirements were challenged in 2010 by three residents of British Columbia on the grounds that they infringe the right to vote of those who do not have the necessary identification. Both the Supreme Court of British Columbia, in 2010, and the Court of Appeal for British Columbia, in 2014, found that while these voter identification requirements did limit the right to vote guaranteed by section 3 of the Charter, this limit was justified under section 1 (Henry v. Canada (Attorney General), 2014 BCCA 30).

The restriction on voting by citizens who had been living abroad for more than five years was challenged by two such Canadians who had not been allowed to vote in the 2011 election. Gillian Frank and Jamie Duong argued that the rule breached the right to vote, contrary to section 3 of the Charter. In January 2019, the Supreme Court of Canada struck down the restriction, saying that it breached the Charter and was not justified under section 1 of the Charter. Meanwhile, on December 13, 2018, Parliament had adopted Bill C-76, which removed the restriction that made electors who had been away from Canada for more than five years ineligible to vote. People applying to the International Register of Electors must prove their identity and Canadian citizenship and must indicate the address of their last place of ordinary residence in Canada.

During the 2019 general election, there were roughly 55,500 international electors registered; about 34,000 ballots were returned, representing 0.2 percent of the total number of ballots cast. This was a marked increase over the 2015 general election, when there were roughly 15,600 international electors registered and about 10,700 ballots returned, representing 0.1 percent of the total number of ballots cast.

The Rights of Candidates and Political Parties

In addition to guaranteeing the right to vote, section 3 of the Charter guarantees the right to be a candidate, subject only to such reasonable limits prescribed by law as can be demonstrably justified in a free and democratic society.

Indeed, under the Canada Elections Act, certain people are disqualified from being a candidate. These include inmates of correctional institutions, federally appointed judges (other than citizenship judges), the Chief Electoral Officer and election officers.

The Charter guarantee of the right to be a candidate led to the challenging and striking down of the requirements for political parties to run a minimum number of candidates in an election and for candidates to make a $1,000 deposit.

When political parties were recognized in law in 1970, the legislation stipulated that for a political party to qualify for registration, it had to run candidates in at least 50 electoral districts. This requirement stood for many years before being challenged under the Charter by Miguel Figueroa, leader of the Communist Party of Canada. The party was deregistered in 1993 because it failed to run 50 candidates in that year's general election. The Supreme Court of Canada's 2003 decision in Figueroa v. Canada ([2003] 1 SCR 912) struck down the 50-candidate requirement as an unjustifiable restriction on the rights guaranteed under the Charter. The Court determined that there was no reason to believe that a political party running fewer than 50 candidates could not act as an effective outlet for the meaningful participation of individual candidates. The ruling also declared that restricting the ability of political parties to register was an unwarranted infringement on the right of citizens to play a meaningful role in the electoral process.

Fifty Candidates Not Needed

In 2003, Communist Party of Canada leader Miguel Figueroa successfully challenged a provision of the Canada Elections Act that required a political party to field 50 candidates in a general election to maintain its registration. Since then, registered parties that field at least one candidate have the right to list their party name on the ballot next to the candidate's name. The Canadian Press, Kevin Frayer

In 2004, Parliament adopted Bill C-3, An Act to amend the Canada Elections Act and the Income Tax Act, implementing new criteria for the registration of political parties. The intent of the bill, introduced by the Liberal government of Paul Martin and supported by the opposition parties, was to strike an appropriate balance between fairness to political parties and the integrity of the electoral system. Among the legislation's innovations was the country's first legal definition of a political party, which it described as an organization one of whose fundamental purposes is to participate in public affairs by endorsing one or more of its members as candidates and supporting their election.

The bill also included new provisions for regulating political activity. Under these provisions, parties are required to maintain at all times a leader, three other officers and at least 250 members. Furthermore, parties must submit an updated list of 250 members and their signed declarations every third year and file a statement once a year outlining the party's fundamental purpose. If a party fails to meet any of these conditions, it risks being deregistered.

In November 2015, Kieran Szuchewycz, who had tried to run as an independent candidate in the 2015 federal election, challenged the requirements to pay a $1,000 refundable deposit and to collect 100 elector signatures, saying these were unconstitutional. In Szuchewycz v. Canada (Attorney General) ([2017] A.J. No. 1112), the Alberta Court of Queen's Bench upheld the signature requirement but ruled that the deposit requirement for prospective candidates infringed section 3 of the Charter. The decision was not appealed, and Elections Canada stopped applying the deposit requirement. In 2018, Bill C-76 amended the Canada Elections Act to remove the deposit requirement.

Freedom of Expression

Election surveys are a familiar feature of modern elections. Concerned that election surveys published late in an election campaign could affect the outcome of an election, in 1993 Parliament adopted legislation banning publication of election surveys during the 72 hours before election day. This provision was challenged in court. In Thomson Newspapers Co. v. Canada (Attorney General) ([1998] 1 SCR 877), the Supreme Court of Canada struck it down as a violation of freedom of expression, ruling that the limits were not justified under section 1 of the Charter.

At the same time, the Supreme Court's ruling indicated that concerns about the methodological accuracy of election surveys were warranted and that it would therefore be constitutional to invoke legislation requiring survey results to be accompanied by details about the methodology used. As a result, the 2000 Canada Elections Act required the first publication of any election survey to include details about the sponsor and the methodology used. The Act also prohibited the publication of the results of new or previously unpublished election surveys on election day.

Staggered Voting Hours

Canada's six time zones once created concern that ballots in eastern Canada were counted and the results broadcast before some voters in western Canada had finished casting their votes. The introduction of staggered voting hours in 2000 largely eliminated this problem—the majority of election results from across the country are now available at approximately the same time. Elections Canada

Meanwhile, growing use of social media and email presented new challenges for controls on the premature release of election results. For many years, the polls opened and closed on election day at a standard hour in every time zone across the country. Ballots would be counted as the polls closed in each time zone from east to west, but voters would learn the results from elsewhere in the country only when the polls closed in their own time zone. When polls closed in Western Canada, voters would often learn that the outcome of the election had already been decided by ballots counted in the rest of the country.

The 1992 report of the Lortie Commission recommended extending voting hours and having staggered hours in different regions of the country. The issue was also recognized by the Chief Electoral Officer. In 1996, the Canada Elections Act was amended to introduce staggered voting hours on election day at a general election so that results would be available at approximately the same time across the country. In 2000, the Act was further amended to empower the Chief Electoral Officer to adjust voting hours in regions that do not switch to daylight saving time.

When a resident of British Columbia named Paul Bryan was prosecuted for posting results of the 2000 general election from eastern provinces before polls in the West had closed, he challenged the constitutionality of the prohibition in section 329 of the Canada Elections Act. The case made it all the way to the Supreme Court of Canada, which held that while section 329 of the Canada Elections Act limited freedom of expression, this limit was justified under section 1 of the Charter.

Ultimately, however, the increasing use of social media made it difficult if not impossible to enforce the prohibition on communicating election results before the polls had closed in western Canada. In his report on the May 2011 general election, the Chief Electoral Officer, Marc Mayrand, said the time had come for Parliament to consider revoking the current rule.

In January 2012, the government announced that it would end the prohibition, saying, The ban, which was enacted in 1938, does not make sense with the widespread use of social media and other modern communications technology.

In 2014, section 329 was repealed.

The Vote and the Voting Process

The guarantee of the right to vote means not only lifting the restrictions on various groups, but also ensuring that barriers to exercising this right are identified and addressed. Over time, legislative and administrative measures have been made to ensure that all voters are able to exercise their right to vote, that the integrity of the voting process is preserved and that constituency boundaries are adjusted to provide effective representation while reflecting the country's diversity.

From Metal to Cardboard

Recyclable cardboard ballot boxes first replaced the traditional metal ones at the 1988 general election in Quebec and Ontario and then at the 1992 federal referendum in the rest of the country. Developed by the National Research Council at Elections Canada's request, the cardboard boxes are lightweight and economical to produce. They can be shipped flat for easy assembly by polling station staff as needed, eliminating the need to store boxes between elections. The cardboard voting screens were also redesigned to include an upper flap, which increases privacy and protects the secrecy of the vote. Elections Canada

Cardboard ballot box

Elections Canada

Cardboard voting screen

Elections Canada

Accessibility of the Vote

Throughout the 1980s, the disability rights movement in Canada pushed for legislative reform to enable full and equal access to all federal programs for people with physical disabilities. Certain features of the electoral legislation made voting physically impractical for many electors.

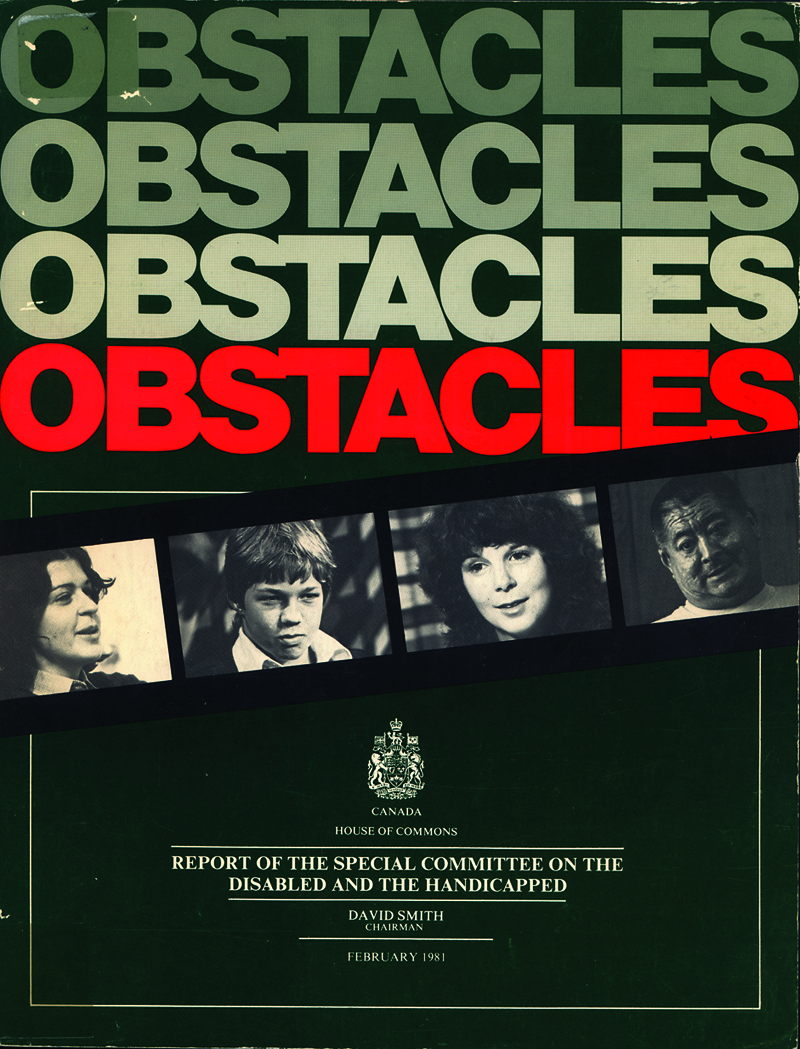

Removing Barriers to Voting

Obstacles, the 1981 report of the House of Commons Special Committee on the Disabled and the Handicapped, recommended that Canada establish a postal vote system

and that the Chief Electoral Officer accommodate the mobility problems of disabled persons.

It also recommended amending the Canada Elections Act to include provision for special polls at hospitals and nursing homes.

These measures were adopted by Parliament when it passed Bill C-78 in 1992 and Bill C-114 in 1993. House of Commons, Special Committee on the Disabled and the Handicapped, Obstacles, Third Report, 1st Session, 32nd Parliament, 1981.

By the early 1990s, the matter had caught Parliament's attention. A report entitled A Consensus for Action: The Economic Integration of Disabled Persons, published by the House of Commons Standing Committee on Human Rights and the Status of Disabled Persons in June 1990, proposed identifying all legislation that presented a barrier to people with physical disabilities. In September 1991, the Canadian Disability Rights Council submitted its own legislative proposals. Based on those proposals–together with the work of the Standing Committee and recommendations from the Lortie Commission, the Special Committee on Electoral Reform and the Chief Electoral Officer–the Progressive Conservative government of Brian Mulroney introduced Bill C-78. Passed by Parliament in 1992, it made a number of amendments to electoral law and administration that made voting more accessible to people with disabilities.

Bill C-78, An Act To Amend Certain Acts With Respect To Persons With Disabilities

Here is a summary of the changes contained in the Act:

- It provided for polling stations at institutions where seniors and persons with disabilities live so election officers could take a ballot box to people who might have difficulty getting to the regular polling place.

- It guaranteed level access at all polling stations and the returning office; unavoidable exceptions would be permitted only with the authorization of the Chief Electoral Officer.

- It introduced transfer certificates that allow people with disabilities to vote at a different poll if their own does not have level access.

- It required templates to be available for the use of voters who are blind or have impaired vision.

- It enabled election workers to appoint language or sign language interpreters to assist them in communicating with electors.

- It allowed election workers to assist an elector with a disability in voting, including marking a ballot on the elector's behalf, in the presence of a witness.

- It mandated public education and information programs for Canadians with disabilities.

Bringing the Ballot Box to Voters

In 1992, Bill C-78 made access to the vote easier in a number of ways. Among the improvements were mobile polling stations that serve many seniors and persons with disabilities in the institutions where they live. Elections Canada

In 2008, James Hughes, a resident of Toronto who used a wheelchair or a walker, made a complaint to the Canadian Human Rights Commission about the lack of barrier-free access to his polling location. In 2010, The Canadian Human Rights Tribunal found that Elections Canada had failed to provide barrier-free access and to address Mr. Hughes' complaints. The Tribunal ordered Elections Canada to make systemic remedies, including consultation with the disability community; improved policies, communication, signage and training; and a dedicated accessibility complaint process (2010 CHRT 4). In 2014, Elections Canada formalized its outreach with the disability community by launching an Advisory Group for Disability Issues to provide subject matter expertise and advice on accessibility initiatives.

Further improvements were made in 2018, when Bill C-76 amended the accommodation measures in the Canada Elections Act to include all persons with disabilities, not only those with physical disabilities. Instead of requiring premises to have level access,

for example, the amendments required them to be accessible to electors with a disability.

Bill C-76 also increased the availability of transfer certificates to electors with disabilities and required the Chief Electoral Officer to develop, obtain or adapt voting technology for use by electors with a disability

and to test the technology for future use in an election. Elections Canada also developed a new paper ballot with larger font sizes to allow electronic screen readers to read the ballot.

Accessibility for Voters with Visual Disabilities

Voters with visual disabilities can use a tactile and braille voting template that has a series of holes, one for each candidate. The template enables these voters to find by touch where to mark their ballot for the candidate they prefer. Elections Canada

Braille voting template

Elections Canada

Advance Voting and Special Ballots

Meanwhile, other legislation during this period improved access to the vote for all Canadians. In 1993, Bill C-114 made advance poll voting available to all citizens. With this change, Canadian voters increasingly took advantage of the early opportunity to cast a ballot. Before the change, just over 500,000 Canadians (3.8 percent of electors) voted at advance polls during the 1988 general election; that number rose to 633,000 (4.6 percent) in 1993. As shown in the following table, since 1993 the numbers and percentages of those voting at advance polling stations and under special voting rules have tended to rise. In particular, there was a steep rise in the percentage of electors voting at advance polling stations from the mid-2000s, when it was roughly 11 percent, to over 26 percent in 2019.

Table 4.1

| Year of General Election | Voting at Advance Polling Stations | Voting Using Special Ballots | Total Votes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Percentage | Number | Percentage | ||

| 1988 | 507,487 | 3.8% | 159,965 | 1.2% | 13,281,191 |

| 1993 | 633,464 | 4.6% | 208,479 | 1.5% | 13,863,135 |

| 1997 | 704,336 | 5.3% | 135,458 | 1.0% | 13,174,698 |

| 2000 | 775,157 | 6.0% | 191,833 | 1.5% | 12,857,773 |

| 2004 | 1,248,469 | 9.2% | 246,011 | 1.8% | 13,564,702 |

| 2006 | 1,561,039 | 10.5% | 438,390 | 3.0% | 14,817,159 |

| 2008 | 1,520,838 | 11.0% | 253,069 | 1.8% | 13,834,294 |

| 2011 | 2,100,855 | 14.3% | 279,355 | 1.9% | 14,723,980 |

| 2015 | 3,657,415 | 20.8% | 607,152 | 3.5% | 17,591,468 |

| 2019 | 4,840,300 | 26.6% | 643,462 | 3.5% | 18,170,880 |

Source: Elections Canada, Past Elections.

Voting While Serving Far Away

Members of Canada's military are able to vote in a federal election, regardless of where in Canada they are stationed or whether they are serving in a foreign land. Canadian Armed Forces members—as well as teachers and administrative support staff at armed forces schools outside Canada—vote by special ballot. For example, Canadians serving in Afghanistan received ballots and the list of candidates for the 2004 general election. They voted a few days before most Canadians so that their ballots could be sent back to Canada in time for counting. Cpl. John Bradley, 3 R22eR Bn. Gp., Dept. of National Defence

In addition, Bill C-114 effectively replaced proxy voting by allowing all electors to vote using the special ballot. The special ballot is a registration and voting system for Canadians who are away from their home ridings, people with disabilities, prison inmates and any other elector who cannot vote in person on election day or at an advance poll. Electors can vote using the special ballot at any local Elections Canada office or by mail. Incarcerated electors, Canadian Forces electors and electors temporarily in hospitals are also able to vote by special ballot on specific days during the election period. The amendments meant that all Canadians living or travelling outside the country–not just military personnel and diplomats–could now vote, as long as they applied for the special ballot before the deadline.

The provisions for advance polling and special ballots were modified in 2014, when Bill C-23, the Fair Elections Act, added a fourth day of advance polling and in 2018, when Bill C-76 extended the hours of advance polls and removed the stipulation that Canadians living abroad must not have been absent for more than five years.

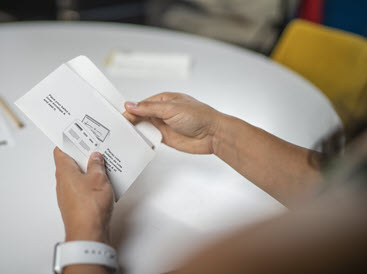

Voting by Special Ballot

Electors who are unable to vote at advance polls or on election day can vote using a special ballot either by mail or, as shown here, in person at a local Elections Canada office. Those voting by special ballot use a unique system of three "nested" envelopes to preserve the secrecy of their choice. Elections Canada

Special ballot voting kit

Elections Canada; ACU00623_C

Fixed-Date Elections

Under Canada's system of responsible government, to remain in office, the Prime Minister and Cabinet must enjoy the confidence–that is, the support–of the majority of the members of the House of Commons. If the government loses the confidence of the House, by convention it would have to resign or seek the dissolution of Parliament, which would trigger a general election. Another feature of this form of responsible government has been that the Prime Minister could seek the dissolution of Parliament at any time.

The Constitution Act, 1867 does not specify when elections must be held. Section 50 provides that five years is the longest the House of Commons can continue. As we saw earlier, this is reiterated in section 4(1) of the Charter, which says, No House of Commons and no legislative assembly shall continue for longer than five years from the date fixed for the return of the writs at a general election of its members.

The only exception to this would be in time of real or apprehended war, invasion or insurrection.

Given the lack of certainty about when elections were to be held, the idea of fixed-term parliaments was debated on several occasions. For example, this idea was supported by the Special Joint Committee of the Senate and the House of Commons on the Constitution of Canada in its February 1972 final report. The Lortie Commission also looked at the idea and summarized the arguments for holding federal elections on a fixed date as follows:

It would make it easier to administer and organize elections; it would allow for better enumeration; and it would be more democratic because it would remove the ability of the party in power to call an election at the most favourable time.

Nevertheless, the Commission did not make any recommendation on fixed-date elections. Neither did the House of Commons Standing Committee on Procedure and House Affairs when it studied the matter in 1994.

The idea did not go away, however, and during the early 2000s, the legislatures of British Columbia, Ontario, and Newfoundland and Labrador enacted legislation establishing fixed election dates. In 2006, the Conservative government of Stephen Harper followed suit by introducing its own fixed-date election legislation: Bill C-16, An Act to amend the Canada Elections Act. It said that fixed-date elections, would provide for greater fairness in election campaigns, greater transparency and predictability, improved governance, higher voter turnout rates and help in attracting the best qualified candidates to public life.

The Chief Electoral Officer, Jean-Pierre Kingsley, also agreed with having fixed-date elections. In his appearance before the House of Commons Standing Committee on Procedure and House Affairs on September 26, 2006, he said that the bill would improve our service to electors, candidates, political parties and other stakeholders.

The bill received royal assent on May 3, 2007.

The amendments to the Canada Elections Act provide for a general election to be held on a fixed date: the third Monday of October in the fourth calendar year following the previous general election. At the same time, the amendments specify, Nothing in this section affects the powers of the Governor General, including the power to dissolve Parliament at the Governor General's discretion.

In other words, the Canada Elections Act does not prevent a general election from being called at an earlier date, either because the government has lost the confidence of the House or because the Prime Minister has decided to seek the dissolution of Parliament.

While Bill C-16 set the date of the next general election in October 2009, Parliament was dissolved earlier and the election took place on October 14, 2008. The following general election would have been held in October 2012, but once again, Parliament was dissolved earlier; the election was held on May 2, 2011. The first general election to be held in accordance with the fixed-date provision was on October 19, 2015.

The 2015 election was also noteworthy because the election period was 78 days, making it the longest since 1872. In his 2016 recommendations report, the Chief Electoral Officer, Marc Mayrand, pointed out that fixed election days were intended to give Elections Canada time to prepare. He noted that returning officers faced additional staffing pressures and were deprived of the anticipated preparatory period.

As a result, the Chief Electoral Officer said, Imposing a maximum limit on the election period (for example 45 or 50 days) in conjunction with the fixed election date would create a greater measure of predictability for all electoral participants as the fixed date approaches and would better accomplish the goal of a fixed election date.

This issue was addressed by Bill C-76, which established a maximum election period of 50 days.

Another issue that arose was that election day and advance polling days coincided with religious holidays. At various times before the Canada Elections Act was amended to provide for fixed election dates, Elections Canada had consulted with religious communities about this issue and had drawn attention to opportunities to vote early, such as voting by special ballot.

Signing the Writs

The Chief Electoral Officer of Canada, Stéphane Perrault, signed 338 writs, one for each electoral district, for the general election of October 21, 2019. At each election, a document like this instructs every returning officer to conduct an election to choose a Member of Parliament. Elections Canada

In 2019, the date fixed for polling day, as well as some of the advance polling days, fell on Jewish holidays. Some members of the observant Jewish community asked the Chief Electoral Officer to consider moving the election date. Elections Canada responded with a statement about how it would accommodate Jewish voters, but did not refer to the power under the Act to recommend an alternate election day. Chani Aryeh-Bain and Ira Walfish then asked the Federal Court for judicial review of the Chief Electoral Officer's decision not to recommend moving the date. The Court ordered him to reconsider his decision and to clearly weigh the impact of his decision on the applicants' rights under section 3 of the Charter (Aryeh-Bain v. Canada (Attorney General), [2019] FC 964). On July 29, the Chief Electoral Officer, Stéphane Perrault, reaffirmed his decision not to recommend to the Governor in Council to change the election date, saying:

Having carefully considered the impact of holding the election on October 21 on the ability of observant Jews to participate in the electoral process, and having balanced that with my mandate to ensure accessible voting opportunities for all Canadians, I conclude that it would not be advisable to change the date of the election at this late stage.

The National Register of Electors

First broached in the 1930s, the permanent register of electors became a reality during the 1990s. Prior to its creation, every time an election was called, the list of those eligible to vote was prepared by enumerators going door to door. The 1986 White Paper on Election Law Reform had examined the issue, but ultimately recommended that the existing enumeration approach be retained. It was the 1989 Auditor General's report–critical of Elections Canada for not using computer technology to streamline its operations–that motivated the push for the long-elusive permanent list.

Following some tests of the software for computerized voters lists, in 1992 Elections Canada used computerized voters lists for the referendum on the Charlottetown Accord in 220 electoral districts, excluding Quebec.footnote 2 The Referendum Act was later amended to permit the use of the 1992 voters lists for the 1993 general election.

The idea of creating a permanent register of electors received a further boost from the recommendations made by the Lortie Commission in its 1992 report, even though it judged that conditions were not yet right for setting up a federal register. The Commission heard that Canadians did not favour moving to a system where it was up to individual voters to register. It also heard from experts that voluntary registration could create obstacles to voting. Ultimately, the Commission recommended that provincial lists of electors be used for federal purposes.

A 1996 report by an Elections Canada working group indicated that such a register would be both feasible and cost-effective, could shorten the election period by eliminating enumeration and could significantly reduce costs and duplication of effort across Canada. That autumn, the Liberal government of Jean Chrétien introduced Bill C-63, which amended the Canada Elections Act to enable the necessary administrative changes. With the bill's passage in December, Elections Canada was given the mandate to create Canada's National Register of Electors.

In preparation for the 1997 general election, Elections Canada conducted its final door-to-door enumeration. Because provincial elections had recently been held in Alberta and Prince Edward Island, lists from those provinces were used for the preliminary lists of electors. The National Register of Electors became a reality after this enumeration and was used for the first time during the 1997 election.

Since that enumeration, the Register has been updated regularly with data from a variety of sources, obtained through information-sharing agreements negotiated by the Chief Electoral Officer. Data-sharing partners of the Register include provincial and territorial motor vehicle and vital statistics registrars and, federally, the Canada Revenue Agency; Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada; and National Defence. Together, these sources update the addresses of the millions of Canadians who move each year–in 2018, 5.2 percent of 15 million households had moved within the past five years. They also identify the names of new electors who turn 18 years of age or acquire Canadian citizenship, and those who die and must be removed from the lists. Elections Canada also updates the Register from the electoral lists of the six provinces and territories that still use some form of enumeration, and the agency normally visits some 10 percent of households in targeted revision initiatives during federal elections. Also, when a general election or by-election is under way, voters can register at their local Elections Canada office or at their polling place when they go to vote. The Canada Elections Act includes strict limits on how personal information from the National Register can be used.

Thanks to the various methods for collecting information and keeping the Register current, it includes the large majority of Canadian electors and is for the most part accurate. Between 2009 and 2020, national coverage–the percentage of electors included in the Register–varied between 92 percent and 96.9 percent (Elections Canada, Description of the National Register of Electors). At the start of the 2019 general election, the coverage was 96.4 percent. The accuracy of the Register–the proportion of registered electors whose address is current–was 93.3 percent at the start of the 2019 general election, compared with 91 percent in 2015 and 90 percent in 2011 (Elections Canada, Report on the 43rd General Election of October 21, 2019).

From its conception, a primary goal of the National Register of Electors was to minimize duplication of effort between elections and across jurisdictions, thereby reducing costs for the taxpayer. According to a statement by the Chief Electoral Officer to the Standing Senate Committee on National Finance on February 8, 2005, concerning its use in the 2000 and 2004 general elections, the Register was estimated to have saved $100 million.

By eliminating the need to conduct a full enumeration with each election, the Register enabled another change long advocated by many voters: the shortening of election campaigns. In 1997, the minimum length of time required between the issue of the election writs and polling day was reduced from 47 to 36 days, and this standard has remained in effect. Election campaigns could, however, be longer–indeed, the 2015 campaign lasted a record 78 days. In 2018, Bill C-76 set a maximum 50-day election period.

Bill C-76 also established a Register of Future Electors in which Canadian citizens 14 to 17 years of age can apply to be included. Upon turning 18, eligible individuals are added to the National Register of Electors. The preregistration of 16- and 17-year-olds was one of the recommendations from the Chief Electoral Officer following the 2015 general election.

The current approach assumes that an enumeration must be as complete as possible if voter registration is to achieve full coverage. This ignores the fact that revision and election-day registration are integral components of a comprehensive process of registration.

Registering at Home

While most information for the voters lists comes from the National Register of Electors, targeted revision of high mobility and low registration areas is conducted during the election period. Revising agents visit new subdivisions, apartment buildings, student residences, nursing homes and chronic care hospitals. The effectiveness of door-to-door canvassing is declining because increasing numbers of people are away from home during the day and there is growing reluctance to open doors to strangers. Elections Canada

Identification Requirements

One of the most significant changes to voting practices in the mid-2000s was the introduction of the need for voters to provide proof of identity and address to register for and vote in a federal election.

The Canada Elections Act of 2000 standardized the process by which voters could register on the day of an election. Since 1993, voters had been permitted to register on election day, but only rural voters had the option to qualify, without documented evidence of identity and address, by simply making a sworn statement and having any other elector registered in that polling division vouch for them. The revised Canada Elections Act extended this option to urban voters as well.

The requirement to show identification was the result of concerns about the integrity of the electoral process. In June 2006, the House of Commons Standing Committee on Procedure and House Affairs tabled a report entitled Improving the Integrity of the Electoral Process: Recommendations for Legislative Change. Saying that concerns had been expressed about the potential for fraud and misrepresentation in voting,

the Committee noted that other important activities required people to show identification. It went on to say:

Traditionally, Canada has tried to make voting as easy as possible, but if confidence in the system is undermined, it becomes necessary to make changes. Obviously, it is not our intention to impose any measures that would discourage voting, nor do we want to make voting more difficult than necessary. The credibility and legitimacy of the system, however, require that procedures be adopted to ensure that only those persons who are entitled to vote do so, and that they are who they say they are. This is essential to preserve the integrity in the electoral system.

The Committee also said that all of the political parties then represented in the House of Commons supported a more effective method of ensuring voter identification, including photo identification, with alternatives available for persons who are unable to furnish the required identification.

In his appearance before the Committee on June 13, 2006, the Chief Electoral Officer, Jean-Pierre Kingsley, said he was in favour of the idea that voters have to present identification when voting.

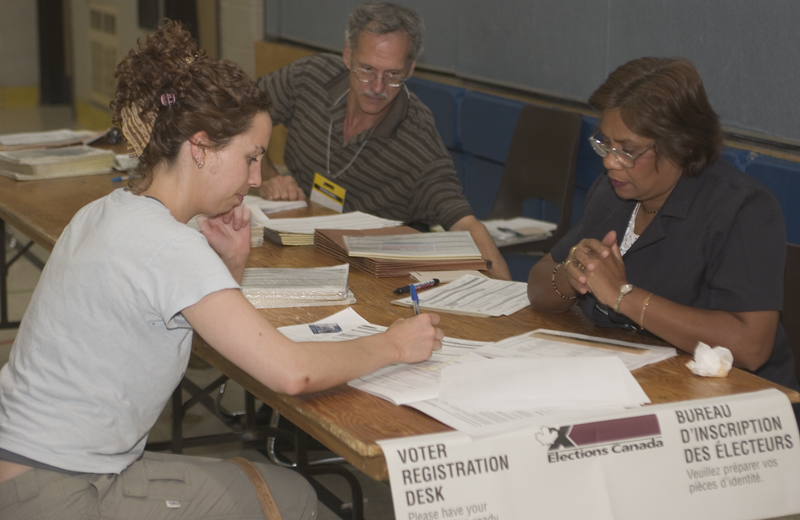

Registering at the Polls

Canadians who are not already on the voters lists can register when they go to vote at the advance or election day polls. Under the rules in place in 2020, they must present proof of their identity and residence; or they may declare that information and have someone who knows them and who is assigned to their polling station vouch for them. Elections Canada

In its response, the government said it would introduce a bill that would implement a uniform system of voter identification at the polls. Bill C-31, An Act to amend the Canada Elections Act and the Public Service Employment Act, which was adopted on June 22, 2007, introduced voter identification requirements, including proof of identity and address. To prove these, electors could choose one of three ways:

- Provide one piece of identification, issued by a Canadian government (federal, provincial/territorial or local). It must show the elector's photo, name and address.

- Provide two pieces of identification, both showing the elector's name and one also showing the elector's address.

- Swear an oath and be vouched for by an elector whose name appears on the list of electors in the same polling division and who has proven their own identity and address.

These requirements caused a problem for electors living in rural areas who did not have identification documents showing their civic address. To deal with this problem, the government introduced Bill C-18, An Act to amend the Canada Elections Act (verification of residence) to allow the use of another type of identification document. Bill C-18 was adopted on December 14, 2007.

In 2014, the identification requirements were modified by provisions of Bill C-23. Adopted by Parliament on June 19, 2014, it prohibited using the voter information card as a piece of identification at the polls. The bill also eliminated the ability of an elector to prove their identity through vouching; this was replaced with an attestation process that still required proof of identity and under which another elector could attest to the elector's address.

Key Provisions of Bill C-23, the Fair Elections Act (2014)

- prohibited the voter information card as a piece of identification authorized by the Chief Electoral Officer

- replaced previous vouching provisions with a procedure for attestation of an elector's address but not the elector's identity

- added a fourth day of advance polling on the Sunday, the eighth day before polling day

- moved the Commissioner for Canada Elections from Elections Canada to the Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions

- introduced a new requirement for an independent audit of poll worker performance following an election

- introduced a new regime regarding voter contact calling services

- changed the tenure of the Chief Electoral Officer to a 10-year, non-renewable term

- introduced new provisions allowing the Chief Electoral Officer to issue interpretation notes, guidelines and written opinions on applying the Canada Elections Act

- the Chief Electoral Officer's mandate to implement public education and information programs to make the electoral process better known restricted to students at the elementary and secondary levels

However, the voter identification requirements were modified once again in December 2018 when Parliament adopted Bill C-76. It lifted the prohibition on using the voter information card as proof of address and restored vouching for electors with no identification documents.

Key Provisions of Bill C-76, the Elections Modernization Act (2018)

- established a maximum election period of 50 days

- extended advance poll hours to 12 hours on each of the 4 days

- reduced the minimum age of election officers to 16

- replaced the word

sex

with the wordgender

throughout the Act - established the Register of Future Electors

- removed the prohibition on using the voter information card as proof of address when used with another piece of identification establishing the elector's identity

- introduced the ability to vouch for an elector's identity and address (and removed the ability to attest to address)

- replaced the requirement for

level access

with the requirement for premises to beaccessible to electors with a disability

- removed the requirements that electors living abroad must have been away from Canada for less than five consecutive years and that they must intend to return to Canada

- repealed legislative provisions that had been struck down by the Supreme Court of Canada's 2002 Sauvé decision regarding voting by prisoners serving a term of two years or more

- restored the Chief Electoral Officer's education and information mandate

- created a pre-election period before fixed-date general elections with new spending limits and reporting requirements for regulated political entities

- expanded the third-party regime by regulating new activities and enacting new reporting requirements and a prohibition on using foreign funds for partisan activities, partisan or election advertising, or election surveys

- required political parties to publish–and maintain–on their website their policy for the protection of personal information

- required some online platforms to maintain a publicly accessible registry of election and partisan ads

- relocated the position of Commissioner of Canada Elections within the Office of the Chief Electoral Officer and granted the Commissioner additional powers

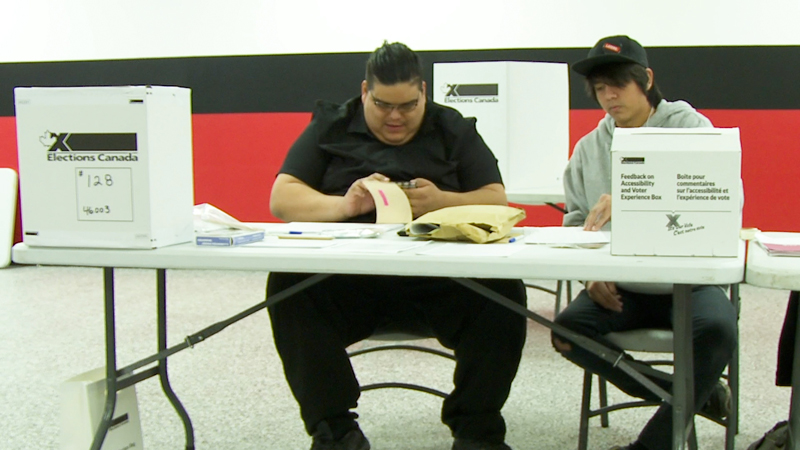

Integrity of the Voting Process

In addition to the new identification requirements first introduced in 2007, further changes to Elections Canada's practices related to the integrity of the voting process were brought about by two court cases. These cases arose out of incidents during the 2011 general election that involved administrative procedures at polling stations and fraudulent telephone calls to voters.

The first case involved a judicial recount in the Ontario riding of Etobicoke Centre. After it was declared that Ted Opitz had won by 26 votes, the second-place candidate, Borys Wrzesnewskyj, contested the result in the Ontario Superior Court of Justice. On May 18, 2012, the Court, which found that election officers had made a number of administrative errors, declared the results of the election null and void.

Mr. Opitz appealed the decision to the Supreme Court of Canada. In a split decision delivered on October 25, 2012, the Supreme Court ruled in his favour and confirmed the original election result.

The case centred on what administrative errors should be considered irregularities that affected the result of the election.

The majority of the judges held that only votes cast by persons not entitled to vote are invalid,

while the minority thought the election could be annulled if there were sufficient administrative irregularities–in other words, failures to comply with the requirements of the [Canada Elections] Act.

To resolve the issue, the Supreme Court established two conditions for invalidating a vote: first, there was a breach of a statutory provision designed to establish the elector's entitlement to vote

and, second, someone not entitled to vote, voted.

If the number of votes invalidated is equal to or greater than the successful candidate's plurality, the election result is annulled.

In this case, the Court did not find sufficient evidence to show that the administrative errors had resulted in voting by people not entitled to vote. At the same time, the Court found that election officers made many serious errors and that, in other circumstances, such errors could lead to an election being overturned (Opitz v. Wrzesnewskyj, 2012 SCC 55). While this court case was under way, Chief Electoral Officer Marc Mayrand said Elections Canada would place a major priority on strengthening measures aiming to improve compliance with procedures and standards applicable on voting days.

(Harry Neufeld, Compliance Review: Final Report and Recommendations, Elections Canada, 2013, p. 11.)

To assist it in improving its administrative practices, Elections Canada commissioned Harry Neufeld, an independent elections expert, to conduct a review of compliance by election officers with election day procedures. His March 2013 final report found that irregularities had occurred for 1.3 percent of all cases of election day voting, an average of 500 administrative errors per electoral district. He recommended the redesign of the voting process to reduce the risk of errors.

Bill C-23 introduced a new requirement for an independent audit of poll worker performance following an election. In 2015–16, Elections Canada set up an internal directorate to oversee compliance with voting procedures and enhance its ability to detect, analyze and respond to incidents that could affect the integrity of the electoral process.

(Elections Canada, 2015–16 Departmental Performance Report.) As well, for the 2015 general election, procedural changes were made to improve compliance at polling stations, more central poll supervisors and registration officers were hired, and training material for poll workers was revised. Additional enhancements were introduced for the 2019 general election, including streamlining and simplifying certificates and forms, further improving the training program and materials, and increasing the support role of the central poll supervisor. At both the 2015 and 2019 general elections, no incidents were detected that interfered with the integrity of the electoral process, and the independent audits confirmed that election officials properly performed their duties at the polls.

The second case related to the integrity of the voting process involved automated telephone calls (so-called robocalls) made during the 2011 general election that gave voters false information about the location of their polling stations. A former Conservative Party staffer was ultimately convicted of trying to prevent electors from voting at the election.

As a result of these fraudulent calls, the Federal Court was asked to annul the election results in six ridings. In his May 23, 2013, ruling, Justice Mosley found that fraud had occurred but said he was not satisfied that the fraud had affected the outcomes in the ridings. He therefore declined to exercise his discretion to annul the results. He noted, however, that had the successful electoral candidates or their agents been implicated in the fraudulent activity, he would not have hesitated to annul the result (McEwing v. Canada (Attorney General), 2013 FC 525).

Also as a result of the robocalls case, Bill C-23 introduced a new regime to ensure transparency when calling service providers contact voters during an election period. Under this regime, the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) is responsible for establishing, maintaining and enforcing the Voter Contact Registry. Those making calls related to the election during the election period must register with the CRTC. They must also keep records of the telephone numbers they call and copies of scripts and recordings used during the calls. Bill C-23 also made it an offence to impersonate candidates or election officers and to fail to follow the obligations to keep scripts and recordings.

In the lead-up to the 2019 general election, new concerns arose about threats to the security of the vote from influence campaigns, disinformation or cyberattacks. In a report entitled Cyber Threats to Canada's Democratic Process, which was published in 2017 and updated in 2019, the Communications Security Establishment (CSE) identified threats posed by foreign adversaries to elections, political parties and politicians, and traditional and social media. CSE, which provides information technology security services to the Government of Canada, said that Canadian voters would likely encounter foreign cyber interference related to the 2019 federal election. However, it noted that while elections around the world had faced cyber threats, Canada's federal elections are largely paper-based and Elections Canada has a number of legal, procedural, and information technology (IT) measures in place that provide very robust protections against attempts to covertly change the official vote count.

(Communications Security Establishment, 2019 Update: Cyber Threats to Canada's Democratic Process, p. 5.)

In response to these concerns, Bill C-76 included provisions to combat emerging threats related to digital interference and disinformation. For example, it prohibited third parties from using funding from foreign entities to conduct partisan activities or partisan or election advertising. It also required major online platforms that sell advertising to political entities during the pre-election and election periods to maintain a registry of that advertising.

In January 2019, the government announced the creation of the Security and Intelligence Threats to Elections Task Force, made up of the Canadian Security Intelligence Service, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, the CSE, and Global Affairs Canada. As an independent agency, Elections Canada was not part of the task force, but it collaborated with these organizations and took measures to improve the security of the vote, such as by improving its information technology infrastructure and providing security awareness training to Elections Canada staff.

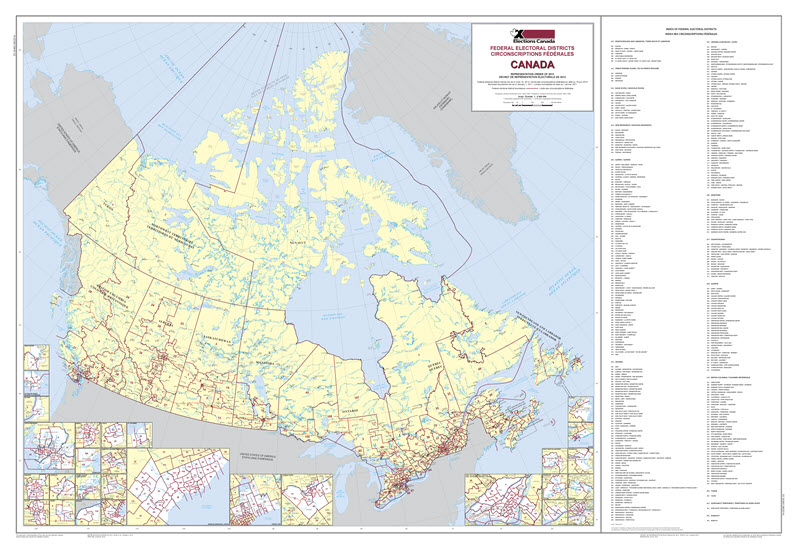

Electoral Districts per Province and Territory

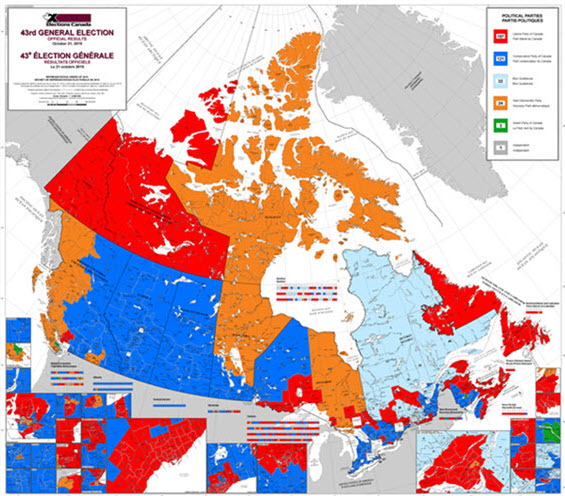

In 2015, the number of electoral districts (and seats in the House of Commons) rose to 338. Additional districts, reflecting changes in population, were allocated to Ontario (15), British Columbia (6), Alberta (6) and Quebec (3). Elections Canada

Boundary Redistribution

As we saw in Chapter 3, the Electoral Boundaries Readjustment Act of 1964 established an impartial process for redrawing constituency boundaries. With continual population shifts occurring since the 1970s, this process led to new seats being created in southern urban areas of the country at the expense of remote northern and rural ridings, as well as of some established and historic ridings in urban cores. The formula for calculating seats is set out in the Constitution Act, 1867; it was revised in 1974, in 1985 and in 2011.

Under the Electoral Boundaries Readjustment Act, commissions draw constituency boundaries so that the population of each electoral district is as close as is reasonably possible to the average population size of a district for that province. Commissions must make every effort to ensure that no constituency deviates from the average by plus or minus 25 percent. In extraordinary circumstances, however, commissions may exceed these limits. Commissions must also consider other human and geographic factors and may vary the size of constituencies to respect communities of interest or identity, to respect historical patterns of previous electoral boundaries or to maintain a manageable geographic size for districts in sparsely populated, rural or northern regions of the province.

Shifting the Boundaries

The work of determining federal electoral district boundaries following each decennial census is done by 10 independent federal electoral boundaries commissions (one for each province). As Nunavut, the Northwest Territories and Yukon constitute one electoral district each, they do not require commissions. Pictured here is the commission for Ontario at one of its 2002 hearings in London. Will Fripp, Secretary, Federal Electoral Boundaries Commission for Ontario

Ensuing Charter challenges highlighted the concept of community of interest.

The most significant case was the 1991 Reference re Prov. Electoral Boundaries (Sask.) ([1991] 2 SCR 158, also known as Carter). The case was put forward on behalf of a group of Saskatoon and Regina voters seeking a court ruling on the constitutional validity of the electoral boundaries that Saskatchewan adopted after The Representation Act, 1989 became law.footnote 3 In reversing a decision by that province's court of appeal, the Supreme Court of Canada held that strict population count should not be deemed the only consideration in defining equitable electoral district boundaries. The Court ruled that the purpose of the right to vote enshrined in section 3 of the Charter is not equality of voting power per se, but the right to 'effective representation,'

which could be achieved by relative parity of voting power,

taking into account factors such as geography, community history, community interest and minority representation to ensure that our legislative assemblies effectively represent the diversity of our social mosaic.

Another case highlighting the concept of community of interest was Raîche v. Canada (Attorney General) (2004 FC 679), in which the Federal Court held that the Federal Electoral Boundaries Commission for New Brunswick had erred in its application of the rules governing the preparation of its recommendations. The Court found that the Commission had not adequately heeded the importance of the Official Languages Act and the communities of interest that existed in the electoral districts. In response to this case, the government introduced Bill C-36, which received royal assent in 2005 and which changed the boundaries of the Acadie–Bathurst and Miramichi electoral districts. It reversed the transfer of certain Francophone parishes from a majority French-speaking riding to a majority English-speaking one. This was the first time since the Electoral Boundaries Readjustment Act was introduced that a court had ordered an electoral boundary to be changed.

Following the 1991 Census, Parliament suspended the readjustment process twice. In 1992, it did so because the readjustment process could likely not be completed before the next federal election. In 1994, faced with dissatisfaction about the process, the government decided to review the Electoral Boundaries Readjustment Act. As a result, Parliament suspended the readjustment process again. In February 1995, the government introduced Bill C-69, Electoral Boundaries Readjustment Act, 1995. Provisions in this proposed legislation were aimed largely at forging a closer link between the redistribution process and the real needs of the populations it sought to serve. The bill would have provided for redistribution reviews every 5 years, instead of 10, and would have defined the term community of interest

to include

such factors as the economy, existing or traditional boundaries of electoral districts, the urban or rural characteristics of a territory, the boundaries of municipalities and Indian reserves, natural boundaries and access to means of communication and transportation.

Although Bill C-69 was passed by the House of Commons, it died on the Order Paper in the Senate when the 1997 general election was called.

The Standing Committee on Procedure and House Affairs made recommendations for improving redistribution in its April 2004 report to the House. In May 2005, the Chief Electoral Officer, Jean-Pierre Kingsley, issued a report entitled Enhancing the Values of Redistribution. It made recommendations on, among other things, ensuring the timely conclusion of redistribution, enhancing the effective representation of Canadians and improving the amount and quality of public input. The report also supported the calls from the Standing Committee to embed a definition of the term communities of interest

in the legislation.

To address the underrepresentation of the fastest-growing provinces–Ontario, British Columbia and Alberta–in December 2011 Parliament passed Bill C-20, the Fair Representation Act. It created more seats for these provinces as well as for Quebec, to prevent that province from becoming underrepresented.

Key Provisions of Bill C-20, the Fair Representation Act (2011)